By Peg Tyre | Originally Published at TakePart. June 25, 2013

For the last three decades, our schools have been shaped by so-called accountability measures. Standardized tests were meant to make sure students were learning, and schools and teachers were held responsible if kids did not meet the standards.

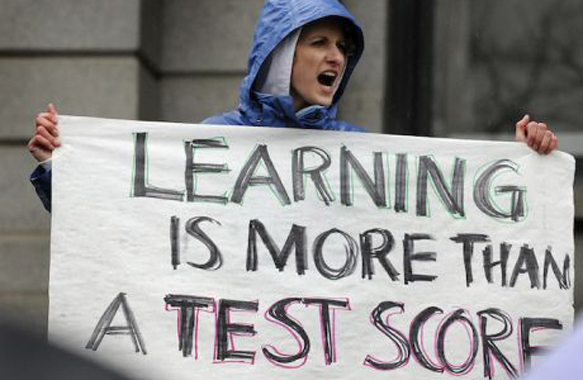

But lately, criticism of the accountability movement and its consequences, intended and otherwise, has reached a crescendo. Parents are pushing back against the testing culture (too much time spent on preparation, testing, and test analysis and not enough on deeper learning).

Policy makers, unable to show broad improvements over time in our schools, have begun to have their doubts as well. Teachers’ unions, which have long protested that it’s misguided and unfair to evaluate teachers by their ability to improve test outcomes, are having their concerns echoed by former accountability gurus like Bill Gates.

Accountability, which once seemed to offer a clean, simple, systematic way to improve education, is fast losing its charm.

So how did we get here?

Well, you can blame Texas. In the 1990s, the state of Texas decided to do something about what they saw as the woeful condition of their schools.

First, they launched a series of exams that high schoolers had to pass to graduate. After that, under the then-governorship of George W. Bush, education officials began testing public school children every year from grades three through eight, and once again in high school.

The scores were separated by race, ethnicity, and other factors; then they were made public. Schools where children did well were rewarded. Schools where children did poorly were shamed, threatened with closure, or shut down.

Related Read; We Must Stop Judging Kids Solely on Standardized Tests

For a while, the accountability movement—with its annual tests and high school graduation exams—seemed to really improve things in Texas. Test scores went up, and dropout rates went down.

In 2000, George W. Bush was elected to the White House, sought bipartisan support for his accountability ideas and turned the so-called “Texas Miracle” into a federal law known as No Child Left Behind. The goal of the law was to have all students in all schools at or above grade level in math and reading.

By 2001, states were charged with coming up with their own standards and then tested students to make sure an increasing number were reaching proficiency in those standards.

The effect was dramatic. For the first time in the history of our country, American citizens began to see in actual numbers just what the achievement gap really looked like. Although special ed kids, poor kids, English-language learners, and kids of color had long performed much worse than middle-class kids, this educational apartheid was largely unspoken and unseen.

Abruptly, the rosy view—that our schools served all children equally well—was torn in two. Schools in low-income neighborhoods where children didn’t learn much were being publicly identified as failing, and middle-class communities found, often to their dismay, just how poorly their schools served some of its subgroups.

By 2006, though, the glow of the Texas Miracle began to fade. Although Texas’ state test scores went up, it was revealed that the dropout rate in the state was much larger than had been reported. Worse, big districts like Houston were monkeying with the numbers—and pushing hard-to-teach kids out of the educational pipelines.

Were the students who remained in schools doing better? It’s debatable, but most indicators suggest they were not. The National Assessment of Educational Program (NAEP), the big federal survey test on student achievement, didn’t budge. And in fact, SAT scores for college-bound Texas seniors actually dropped.

Meanwhile, the rest of the country was going test crazy. NCLB required each state to come up with standards and test kids on whether they were meeting them or not.

According to the Pew Center on the States, annual spending on standardized tests rose from $423 million before NCLB to almost $1.1 billion in 2008. More and more classroom time was devoted to preparing and administering tests. One district counted that 45 days, out of a 180-day school year, were given over to test-related matters.

In addition to the amount of time given over to tests, schools were dumbing down what they taught so more kids would pass. As structured, standardized tests don’t include questions that demand complex analysis, synthesis, or higher order thinking. Instead, the questions are pulled from the bottom third of the curriculum.

NCLB required states to test kids in language and math skills, and the old adage “what gets tested gets taught” turned out to be true.

Some schools, especially in low-income communities where kids had traditionally struggled, became math and language-arts bootcamps. Science, history, and the arts became a luxury school officials felt they could no longer afford. Teachers, whose jobs depended on getting more kids to pass standardized tests, tended to focus students “on the bubble.” Soon enough, cheating scandals took root in major districts.

Kids Tell All: In 5th Grade, I Could Barely Read (VIDEO)

In 2009, Barack Obama announced Race to the Top, his own version of accountability in which states competed for $4.35 billion by instituting reforms aimed at improving test scores. And this year, the old NCLB tests developed by each state are being replaced by exams meant to test a new set of standards agreed upon by all but five states called the Common Core.

But as our schools embark on this latest iteration of accountability, serious questions are being raised about whether our reliance on test scores as our main measure of school success is a sound policy. In May 2011, the National Research Council, which creates guides for policy makers, found no evidence that test-based incentive programs were consistently working.

In Washington, Florida, New York, and the city of Chicago, parents began pushing back on what they saw as the stranglehold of testing culture in their schools. This spring, the Texas state legislature, which launched the accountability movement so many years ago, began scaling back plans to administer even more high school exit exams to students.

So while accountability is at a crossroads, the challenges that face our public school system are increasing. Public school students are becoming increasingly poor and non-English speaking, and the systems we use to improve outcomes for all children remain an open question.

Peg Tyre is the author of two bestselling books on education, “The Trouble With Boys” and “The Good School” and a sought after speaker on educational topics. She has written about education for the New York Times, The Atlantic, Time.com, Newsweek and spent three years as a correspondent for CNN. Currently, she serves as director of strategy for the Edwin Gould Foundation, which invests in organization that get low-income children to and through college. @pegtyre | TakePart.com.

Leave A Comment