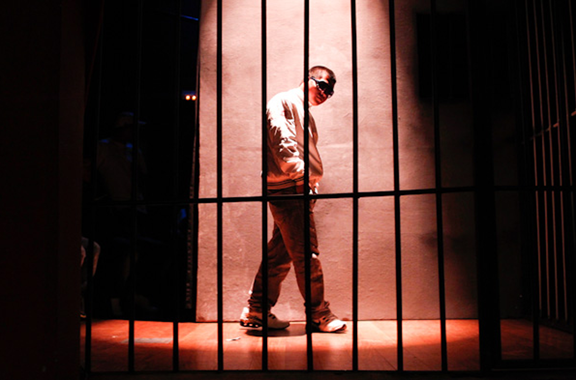

An inmate performs in a play at a public theatre in Lima, Peru. The theatre program is one of many prison activities popping up around the globe to help reduce overcrowding and rehabilitate prisoners. (Photo from Reuters/Enrique Castro-Mendivil)

As tots we were given time to grow. Everyone we encountered wanted us to succeed. We were coaxed. Say “Mama, Dada.” Stand. Sit. Walk. Draw. Run. Dance. Sing. Smile. Wave. And be silly! It is all so cute. Cute to them was great for us, good for us too. We explored and discovered. We found meaning in our experiences. We learned. We grew and all because we had the freedom to express ourselves. No pent up emotions. No sitting still. Our hands were not in cuffs, ankles were not chained, and no steel doors trapped us. We were free to be!

As children we all did as the young do. We colored and painted. Crayons were like candy, even better. We would suck on the sugar of putting pen to page and never develop a cavity! Indeed, rather than create a hole, empty spaces are filled when we play with pigments. Dancing is another delight that comes naturally. Most of us waddled and waltzed before we talked. When we did discover our voice, oh what joy. We could carry a tune even if we could not carry much else. Yes, singing sealed the deal. As young-artists we served a personal master. We had meaningful lives. We were not imprisoned – that is until we fell victim to the system, more specifically the school system.

There

There too the majority die spiritually, or did. A few in California have escaped, ironically, when given the freedom to re-discover the arts. Please ponder the paradigm that is Theater Can Help Solve California’s Prison Overcrowding Crisis and then reflect. Ask yourself, why is it that we remove the Arts from school, suffer the consequences, and then, only to save ourselves from an overcrowding crisis and the costs incurred do we return to the Arts?

Closing the door before the horses escape…Let us draw on the analogy or just draw, paint, play and perform…once again. Let us give the tots within us all the time, space, and tools to grow!

Introduction copyright © 2013. Betsy L. Angert

Can Theater Help Solve California’s Prison Overcrowding Crisis?

Can theater help solve California’s prison overcrowding crisis? The answer is yes.

The recent prison compromise between Gov. Jerry Brown and the state Senate presents California with a unique opportunity to provide a durable, transformative solution to its prison overcrowding problem by focusing on rehabilitation. One reason for the crowding crisis is California’s highest-in-the-nation 63.7 percent recidivism rate. That means for every 1000 inmates that leave prison, 637 commit new crimes and land back in prison.

There is a better way — and it saves taxpayer dollars.

Multiple studies show in-prison rehabilitation programs can significantly reduce the percentage of prisoners who re-offend. If California could reduce its recidivism rate by just 10 percent, that alone would solve the crowding problem. Any successful system of rehabilitation requires multiple components, ranging from mental health and drug treatment to education and skills training. One aspect that may not be initially obvious, however, is the power of art and theater.

Arts-in-corrections programs have helped inmates express and manage their emotions; gain new insights; change destructive behaviors; and transform lives, bringing down the recidivism rate, helping to lessen the chances of new victims and saving the State money.

California used to have a successful statewide arts-in-corrections program. In 1977, Eloise Smith, who was appointed by Brown to serve as the first director of the California Arts Council, established the Prison Arts Project. It was the first of its kind and soon emulated by other states.

The Prison Arts Project program was evaluated in 1983 with a cost-benefit study by Dr. Larry Brewster at the University of San Francisco. The study found the Project to be effective. Taxpayer benefits resulted from fewer incidents and a reduction of disciplinary actions. Additionally, qualitative data – through surveys with inmates, staff and corrections officers — suggested a transformation in attitudes and skill sets among participants.

A 1987 follow-up study by Brewster found that inmates who went through the Prison Arts Project returned to prison at lower rates than the general population of parolees. The study showed that one year after release, Prison Arts Project participants had a favorable status rate of 74.2 percent, compared to 49.6 percent for state parolees as a whole.

Earlier this year, the California Legislative Joint Committee on the Arts held a hearing on the role of art in preventing incarceration. Experts in the field validated the prior successes of the Prison Arts Project and testified that the arts can be an effective tool to slow the prison pipeline and reduce recidivism.

Due to budget cuts, the Prison Arts Project was eliminated in 2003. A few non-profit groups, however, have sustained some arts-in-corrections programs with only private funding. The Actors’ Gang Prison Project is one such example. This non-profit outreach program works with inmates in a handful of California’s prisons. The workshops have 20 inmates, run for eight weeks and are intense, with each session lasting four hours. The prisoners are required to keep a diary so they can map their progress and, at the end of the eight weeks, they open the doors to allow other inmates & invited guests to watch a workshop and hear first-hand the inmate’s experience of transformation.

Thanks to this successful program, some inmates, for the first time, are able to express long repressed emotions or experience and understand new ones. This helps to develop empathy, an essential tool to stop reoffending. Rival prison gang members have developed deep bonds and have transcended race barriers through these acting workshops. What could be seen as merely having fun, actually works on a deep, cognitive level and creates lasting effects in the lives of the inmates, their families and the communities they come back to.

One prisoner who went through the program wrote, “I made a major transition. I got to express my emotions …. I made a real connection with the men here …. It’s made me a better man.”

Another inmate wrote, “This class has brought freedom. When this class starts we have freedom — we can live anywhere and be anything and we’re not confined. We feel ‘normal’ in here this class.”

And, “Barriers are being broken, we are all talking, there is a spirit of peace on the yard.”

While the Actors’ Gang Prison Project has transformed lives without any State funding, to have a significant effect on recidivism reduction, these programs need to be provided statewide. The compromise embodied in Senate Bill 105 offers a path forward for funding on a statewide basis for rehabilitation programs. A federal three-judge panel recently ordered the governor’s administration and attorneys for prisoners to negotiate a solution to the prison crowding crisis. Restoring arts-in-corrections programs on a statewide basis needs to be part of that conversation.

As Shakespeare wrote so insightfully in Hamlet, “[W]e know what we are, but know not what we may be.”

Tim Robbins is an actor, director, and producer and founding Artistic Director of the Actors’ Gang. Ted Lieu is a California state Senator and Chair of the Legislative Joint Committee on the Arts.

Leave A Comment