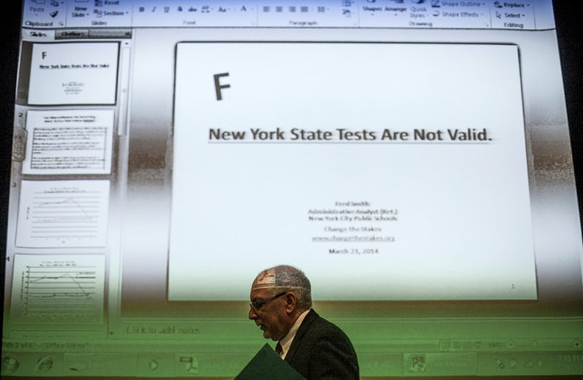

Photograph; David Rapheal, Brooklyn borough assessment implementation director for New York schools, at a meeting on the opt-out movement on Tuesday | Credit Anthony Lanzilote for The New York Times

By Ginia Bellafante | Originally Published at The New York Times. March 28, 2014

In the coming weeks, children in New York City and across the state will begin taking annual standardized tests in math and language that will run over the course of many hours and days, assuming a kind of onerousness once exclusive to the bar exam. Last year, the first in which the tests were aligned with the Common Core, a set of standards intended to determine whether a child is on track to becoming prepared for college, a number of parents, here and nationally, maintained an activist stance against them. About 270 children in the city’s public school system did not sit for the tests, their parents believing that the burdens imposed were hardly offset by the tests’ highly debatable value.

This movement of refusal does not evolve out of antipathy toward rigor and seriousness, as critics enjoy suggesting, but rather out of advocacy for more comprehensive forms of assessment and a depth of intellectual experience that test-driven pedagogy rarely allows. In the past year, the movement has grown considerably among parents and educators, across political classifications and demographics.

At the Brooklyn New School, a highly regarded elementary school in Carroll Gardens that prides itself on academic independence, over 210 students in third through fifth grades — two-thirds of the relevant students — will not take the state-mandated tests this year. This figure includes children in fourth grade for whom state test scores are typically used for middle-school admission. When parents called those schools to which B.N.S. graduates typically go, they were told that opting out of the tests would not damage their children’s chances for acceptance.

The website for the Institute for Collaborative Education, in downtown Manhattan, specifically invites parents of middle-school students to join the opt-out initiative, asking them to demonstrate support for the kind of teaching and learning the school provides, an approach that is antagonistic to rote test preparation. ICE, as it is known, is not the sort of place where students create visual memoirs out of pipe cleaners, but rather one that fosters the knowledge and the style of critical thinking that the Common Core and most sane, intelligent people understand as essential. In sixth grade, the year of entry, children currently combine a study of ancient Rome with an analysis and performance of elements of “Julius Caesar.” In seventh grade, a mock trial is conducted around “Macbeth.”

The most significant aspect of this wave of testing dissent is its expansion beyond the world of affluent white parents and celebrated schools, where children are largely destined to succeed. On Thursday, parents in Harlem gathered to announce their displeasure with a system that has forsaken meaningful education for a culture of obsessive examination. More than 100 families at Hamilton Heights School, an elementary school where 80 percent of students receive free lunch, had sent letters alerting the principal that their children would decline to take the tests. At Public School 446 in Brownsville, Brooklyn, Latoshia Wheeler said her son, a third grader, would not be taking the tests, nor would a majority of his classmates.

“We didn’t know that we had the right,” she said.

What is happening is a revolution not simply against a methodology but in some sense against a class system that to a great extent has left progressive education — with its excited learners immersed for months in astronomy or medievalism or Picasso — the province of those able to send their children to some of the best private schools, or with the means to live in places with leading public schools.

In the early 1920s, when Helen Parkhurst developed the plan on which the Dalton School, a private school on the Upper East Side, is based, she did so with the idea that learning should be intimate, self-directed and thrilling. (“How many class lessons have children to listen to which are boring and useless,” Miss Parkhurst wrote, “and others where they are not sufficiently interested to ask a question?”) And thus it has been for a certain segment of New Yorkers.

As Rosa Perez-Rivera, a mother in the Bronx who is opting out, explained it, her daughter was thrilled by school last year, when work around oceans sparked a love of science. This year, in third grade, as the focus has moved to test preparation (state tests are administered in third through eighth grade), her confidence and enthusiasm have lagged. “Just as she is getting interested in a subject and grasping it, they’re moving on to the next,” Ms. Perez-Rivera said. “She is learning not to trust herself, and it is killing her creativity.”

A mother on Staten Island who has also chosen to opt out lamented that her son had been given little instruction in history since he aged into the universe of mandated testing. It is one of the principles of the Common Core that reading comprehension is foundational, that you cannot, for example, sufficiently understand “Gulliver’s Travels” without knowing something of 18th-century British political history. The irony is that once the grounding subjects are sacrificed to the time-sapping exercise of test preparation, the broader purpose of the philosophy is eviscerated.

Even the tests’ vocal advocates cannot entirely embrace the kind of instructional sentiment the exams have unleashed. In a recent letter to school superintendents, John B. King Jr., the state’s education commissioner, discouraged administrators from making placement and promotion decisions based solely on the tests. Speaking by telephone last week, Dr. King told me, “I worry that there’s a pedagogical mistake made in believing that if there’s more test prep, students will do better on the test.” Dr. King told me. In those fears, he hardly stands alone.

Email: bigcity@nytimes.com

A version of this article appears in print on March 30, 2014, on page MB1 of the New York edition with the headline: Standing Up to Testing.

Leave A Comment