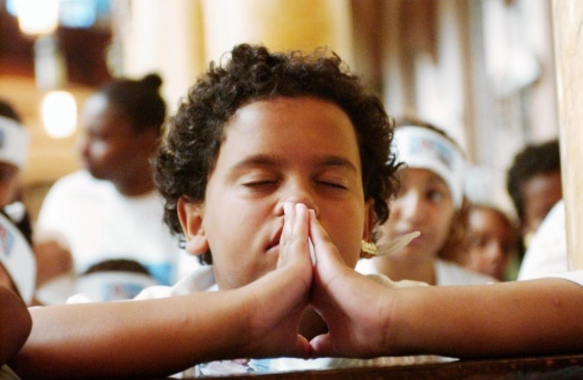

Joshua Cintron, 10, prays during funeral services for his cousin, Naisha Pearson, at St. Luke’s Church in the Bronx. Pearson, 10, was shot and killed by a stray bullet at a neighborhood Labor Day picnic in a Bronx park when a fight between two men erupted in gunfire. | Credit; Michael Schwartz

By Michelle Chen | Originally Published at Al Jazeera America. March 4, 2014 8:00AM ET

To confront the effects of community violence, we must treat psychological trauma too

Dr. Andrew Dennis, a surgeon in the Cook County Hospital trauma unit, examines a man’s year-old gunshot wound, in Chicago in May 2013. A 2012 study found that more than 4 in 10 patients at the hospital who were screened showed symptoms of PTSD, with an even higher rate among those wounded by guns.Daniel Acker/Bloomberg/Getty Images

It has become a media cliche to compare neighborhoods plagued by gun violence to war zones. The combat metaphors range from children caught in the crossfire to explosions of gang warfare to SWAT-like police teams patrolling the streets. But behind the bleak imagery lies the hidden collateral damage of people’s tender psychological wounds: It’s an epidemic of trauma-related stress in the hospitals, schools and living rooms of these beleaguered communities.

A recent investigation by ProPublica highlights a study of hospital patients in inner-city communities in Atlanta that revealed rates of post-traumatic stress (PTSD) symptoms comparable to those seen in veterans of the Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq wars. At least 1 in 3 respondents reported that at some point in their lives they had experienced PTSD symptoms — an array of stress responses including flashbacks, persistent feelings of fear or shame, a sense of alienation and aggressive behavior. (The nationwide PTSD rate is about 7 to 8 percent, with generally higher rates among blacks and women.)

In another study on Chicago’s Cook County Hospital — which tends to thousands of gunshot victims each year — more than 4 in 10 patients screened showed symptoms of PTSD, with an even higher rate among those wounded by guns.

The prevalence of these psychological ripple effects suggests that in some neighborhoods, nearly every family is touched by traumatic violence. Beyond the direct victims of shootings and assaults, those affected include the loved ones of survivors — who struggle to help family members cope with, for example, a spouse’s debilitating panic attacks or a child’s unrelenting nightmares. And they typically carry this weight within a landscape rife with poverty, often without a hospital, much less a psychiatrist’s office, nearby.

Among the most trauma-ridden neighborhoods are impoverished communities of color where inequality fuels hopelessness. That drives vulnerable youths deeper into violence, both as victims and as perpetrators. Studies on youths (PDF) have traced PTSD symptoms back to forms of violence — from street shootings and police chases to sexual assault — that have become routine in rough city neighborhoods.

The troubles facing this population are well known. President Barack Obama recently launched a charity-based program to help young men of color “beat the odds.” Yet many of the conventional approaches to “saving” disadvantaged youth continue to emphasize overcoming the odds and personal responsibility over structural change to social environments.

A survey by the Family-Informed Trauma Treatment Center of so-called inner city kids — who are disproportionately black and Latino — revealed that more than 80 percent (PDF) have experienced “one or more traumatic events.” And their struggles tend to deepen over time because of a lack of accessible culturally appropriate mental health treatment.

According to a 2012 report (PDF) from the Office of the Attorney General’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence, trauma experienced early in life could more than double “the risk and severity of post-traumatic injuries and mental health disorders.” This could in turn harm youths’ long-term development, leading to problems in adulthood, such as anxiety disorders and drug abuse. The most impacted neighborhoods are arguably those where gun violence is routinely dismissed — by politicians and media alike — as an intractable status quo. (After the Sandy Hook shooting, public concern over guns exploded in part because the massacre took place in a relatively privileged Connecticut suburb.)

It’s not surprising that urban violence traumatizes civilians the same way war affects soldiers: Seeing friends gunned down on the way to school is at least as traumatic as watching comrades perish on the front lines. But when the violence ricochets across a community’s fundamental institutions of family, work and education, the cumulative social stress has more insidious effects, undermining people’s ability to work or care for their children. Meanwhile, these embattled communities are often isolated from critical mental health care resources. Studies have found major racial disparities in the quality and availability of mental health care, with whites tending to receive better care for issues like depression and anxiety.

Stopping the cycles of trauma starts with an acknowledgment of community violence not as a mere crime problem but rather as a collective social trauma — both a public health scourge and a moral issue.

Although statistically, blacks and Latinos may face significantly higher risks of exposure to certain traumatic experiences, including childhood maltreatment and, in some cases, war-related trauma, people of color suffering from PTSD are overall less likely than their white peers to seek treatment. The potential barriers are complex and interwoven — basic socioeconomic gaps plus a lack of services nearby; cultural factors such as a general discomfort with formal, white-dominated medical systems or stigma around mental illness (PDF); not to mention, for many immigrants, language barriers.

So in communities where structural hardships drive people into crisis — where concentrated poverty and anemic social service systems lead to family breakdown and social unraveling — people often land in emergency rooms. There are no other social supports. Or they might be shunted into the prison system, where institutional isolation furthers trauma.

According to the National Association for Mental Illness, some 70 percent of youths in state and local juvenile justice facilities suffer from mental health problems (PDF) — part of a broader trend of prisons and jails becoming warehouses for the mentally ill. These youths are in many cases cut off from mental health care and from their communities and families; an untold number will be released back into society as hardened, unstable adults. Aggravating the crisis in communities (PDF), state mental health programs lost more than $4 billion in funding from fiscal year 2009 to 2012 — a cost passed down to the hospitals and courtrooms that ultimately must absorb the burden.

Stopping these cycles of trauma starts with an acknowledgment of community violence not as a mere crime problem but rather as a collective social trauma — both a public health scourge and a moral issue. Holistic solutions could include integrating PTSD screenings of injured patients into the routine treatment process at hospitals or ensuring that children are screened for symptoms through school-based clinics. For people who may have little contact with any health care system except in emergency situations, this might be the only chance to identify people who need treatment early on as well as to measure the overall needs for services across a community.

A more comprehensive anti-violence strategy would focus on every intersection between violence and community life, working with local residents, community groups, schools and health agencies to build resilience against a turbulent social climate.

Many community groups are intuitively building new support systems. Although these programs tend to operate independently — despite some funding from Washington, the implementation of programs is largely directed by state and local agencies — they fold into a broader effort to deal with violence as a public health issue. Even social supports (PDF) that do not directly address violence, such as youth development initiatives in schools and community-based education and employment programs, can stabilize families and help them overcome everyday stressors. In Chicago, community groups and social agencies developed family-based therapy programs that treat children and caregivers in tandem, effectively reducing youths’ overall exposure (PDF) to community violence.

Local activists have recently taken action on their own, for example, by campaigning for a trauma center on Chicago’s South Side, so people can receive care in the areas hardest hit by gun violence. Similarly, youth activists with Youth Organizing to Save Our Streets in Crown Heights in Brooklyn, have resisted gun violence and pushed back against a punitive criminal justice system through youth-led conflict mediation and community education programs on gang involvement and mental health.

The chaos that seems to haunt so many urban neighborhoods does not start with the pulling of a trigger. It represents the fallout of decades of underinvestment in neighborhoods where schools, health care and social services are chronically deprived — the brutality of the everyday, with no bullets, just innocent targets.

Whether they’re in the hospital or behind bars, people who experience these collective traumas should not be treated as acute cases but as casualties of a systemic kind of violence, the pathological inequalities that leave few visible scars but fester below the surface. To treat those wounds, we need more than political prescriptions of getting tough on violence or self-help for teens. Community trauma is part of a lifelong plight. And it is our collective responsibility to stop the bleeding.

Michelle Chen is a contributing editor at In These Times, an associate editor at CultureStrike and a blogger at The Nation. She is a co-producer of “Asia Pacific Forum” on Pacifica’s WBAI and Dissent magazine’s Belabored podcast. She studies history at the City University of New York Graduate Center.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera America’s editorial policy.

I am from the West Side of Chicago and experienced the incredible violence that occurs there. When I was a teen, part of the reason I turned to alcohol and drugs was to cope with that trauma. I was lucky. I had two parents who sent me to Catholic schools and made sure I received an education, but many of those around me were not so fortunate. Many have been involved in the criminal justice system and have been ravaged by drugs and alcohol. We cannot expect poor children to learn the same way as affluent children who have never known the trauma they face almost on a daily basis. Yet, resources for this massive public health problem are sorely lacking. Like the economic depression that poor and working class neighborhoods have experienced for decades, we ignore it. It is racism, but it’s also classism. As long as it doesn’t affect them, the affluent continue to ignore it. What they fail to realize is that the income gap is widening and fewer and fewer people are invested in this discriminatory system. Sooner or later, the majority will refuse to cooperate and the affluent may unfortunately become victims of their own folly.