Project Description

Black White and Red All Over

Who Gets Killed?

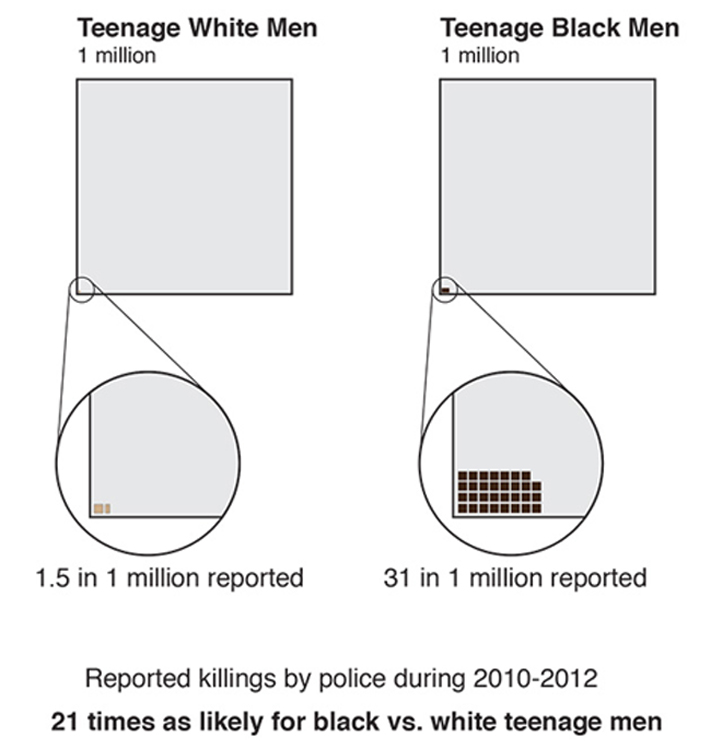

The finding that young black men are 21 times as likely as their white peers to be killed by police is drawn from reports filed for the years 2010 to 2012, the three most recent years for which FBI numbers are available.

A ProPublica analysis of killings by police shows outsize risk for young black males.

The 1,217 deadly police shootings from 2010 to 2012 captured in the federal data show that blacks, age 15 to 19, were killed at a rate of 31.17 per million, while just 1.47 per million white males in that age range died at the hands of police.

One way of appreciating that stark disparity, ProPublica’s analysis shows, is to calculate how many more whites over those three years would have had to have been killed for them to have been at equal risk. The number is jarring – 185, more than one per week.

ProPublica’s risk analysis on young males killed by police certainly seems to support what has been an article of faith in the African American community for decades: Blacks are being killed at disturbing rates when set against the rest of the American population.

Our examination involved detailed accounts of more than 12,000 police homicides stretching from 1980 to 2012 contained in the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Report. The data, annually self-reported by hundreds of police departments across the country, confirms some assumptions, runs counter to others, and adds nuance to a wide range of questions about the use of deadly police force.

Colin Loftin, University at Albany professor and co-director of the Violence Research Group, said the FBI data is a minimum count of homicides by police, and that it is impossible to precisely measure what puts people at risk of homicide by police without more and better records. Still, what the data shows about the race of victims and officers, and the circumstances of killings, are “certainly relevant,” Loftin said.

“No question, there are all kinds of racial disparities across our criminal justice system,” he said. “This is one example.”

The FBI’s data has appeared in news accounts over the years, and surfaced again with the August killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. To a great degree, observers and experts lamented the limited nature of the FBI’s reports. Their shortcomings are inarguable.

The data, for instance, is terribly incomplete. Vast numbers of the country’s 17,000 police departments don’t file fatal police shooting reports at all, and many have filed reports for some years but not others. Florida departments haven’t filed reports since 1997 and New York City last reported in 2007. Information contained in the individual reports can also be flawed. Still, lots of the reporting police departments are in larger cities, and at least 1000 police departments filed a report or reports over the 33 years.

There is, then, value in what the data can show while accepting, and accounting for, its limitations. Indeed, while the absolute numbers are problematic, a comparison between white and black victims shows important trends. Our analysis included dividing the number of people of each race killed by police by the number of people of that race living in the country at the time, to produce two different rates: the risk of getting killed by police if you are white and if you are black.

David Klinger, a University of Missouri-St. Louis professor and expert on police use of deadly force, said racial disparities in the data could result from “measurement error,” meaning that the unreported killings could alter ProPublica’s findings.

However, he said the disparity between black and white teenage boys is so wide, “I doubt the measurement error would account for that.”

ProPublica spent weeks digging into the many rich categories of information the reports hold: the race of the officers involved; the circumstances cited for the use of deadly force; the age of those killed.

Who Gets Killed?

The black boys killed can be disturbingly young. There were 41 teens 14 years or younger reported killed by police from 1980 to 2012 ii. 27 of them were black iii; 8 were white iv; 4 were Hispanic v and 1 was Asian vi.

That’s not to say officers weren’t killing white people. Indeed, some 44 percent of all those killed by police across the 33 years were white.

White or black, though, those slain by police tended to be roughly the same age. The average age of blacks killed by police was 30. The average age of whites was 35.

Who is killing all those black men and boys?

White officers, given their great numbers in so many of the country’s police departments, are well represented in all categories of police killings. White officers killed 91 percent of the whites who died at the hands of police. And they were responsible for 68 percent of the people of color killed. Those people of color represented 46 percent of all those killed by white officers.

What were the circumstances surrounding all these fatal encounters?

Did police always list the circumstances of the killings? No, actually, there were many deadly shooting where the circumstances were listed as “undetermined.” 77 percent of those killed in such instances were black.

Certainly, there were instances where police truly feared for their lives.

Does the data include cases where police killed people with something other than a standard service handgun?

Risk ratios can have varying levels of precision, depending on a variety of mathematical factors. In this case, because such shootings are rare from a statistical perspective, a 95 percent confidence interval indicates that black teenagers are at between 10 and 40 times greater risk of being killed by a police officer. The calculation used 2010-2012 population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

ii https://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1307015-victims-14under-byraceanddecade-spssoutput.html#document/p1/a179431

iii https://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1307015-victims-14under-byraceanddecade-spssoutput.html#document/p1/a179432

iv https://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1307015-victims-14under-byraceanddecade-spssoutput.html#document/p1/a179433

v https://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1307015-victims-14under-byraceanddecade-spssoutput.html#document/p1/a179434

vi https://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1307015-victims-14under-byraceanddecade-spssoutput.html#document/p1/a179435

xxxvii https://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1307298-circumstances-yearcats-spssoutput.html#document/p1/a179463

xl Calculated from the “Weapon Used by Offender” variable. Ranked based on frequency of reported shotgun homicides by police agencies.

xli https://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1307312-offweapon-bystate-spssoutput.html#document/p3/a179466

xlii https://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1307313-offweapon-lapd-spssoutput.html#document/p1/a179467

xliii https://www.propublica.org/documents/item/1307316-offweapon-dallas-spssoutput.html#document/p1/a179468

Ryan Gabrielson is a reporter for ProPublica covering the U.S. justice system. In 2013, his stories for the Center for Investigative Reporting on violent crimes at California’s board-and-care institutions for the developmentally disabled were a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. | Follow @ryangabrielson

Ryann Grochowski Jones is a data reporter at ProPublica. Previously, she was a data reporter for Investigative Newsource/KPBS in San Diego, Calif. She received her master’s degree from the University of Missouri School of Journalism, where she was a data librarian for Investigative Reporters and Editors/National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting| Follow @ryanngro

Eric Sagara is the News Applications Fellow at ProPublica. Prior to that he was a reporter on the Newark Star-Ledger’s data team. He is originally from Arizona, where he reported on business, education, crime and government.. | Follow @esagara

The images, along with the information was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with the kind permission of ProPublica. We are grateful for the research, investigation, and visual illustrations.