Project Description

John Lewis; March: Book One – The Book Reviewed

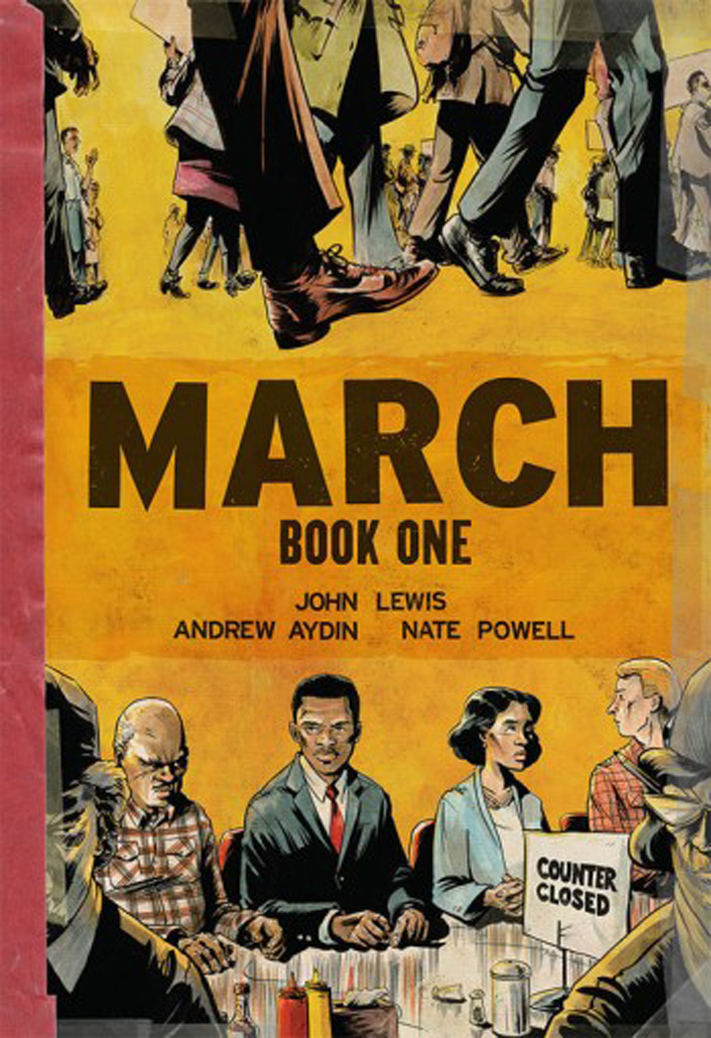

Presenting the story in the form of a graphic novel makes it that much more accessible and immediate for the targeted YA audience; March is a showcase example of the power of the comics medium as an educational tool. As a teenager himself, Lewis drew great inspiration from a ten-cent comic book called Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, published in 1956. He recently told an interviewer that this humble comic was “like a Bible” for him and his fellow activists back then, an indispensable tool for learning how to implement non-violent activism and protest techniques such as passive resistance and sit-ins. Though March deals with important, weighty themes, it never feels didactic, remaining immediate and engrossing throughout. Lewis and his co-writer, congressional staffer Andrew Aydin (who convinced Lewis to present his narrative in the comics format), keep the proceedings simple and linear.

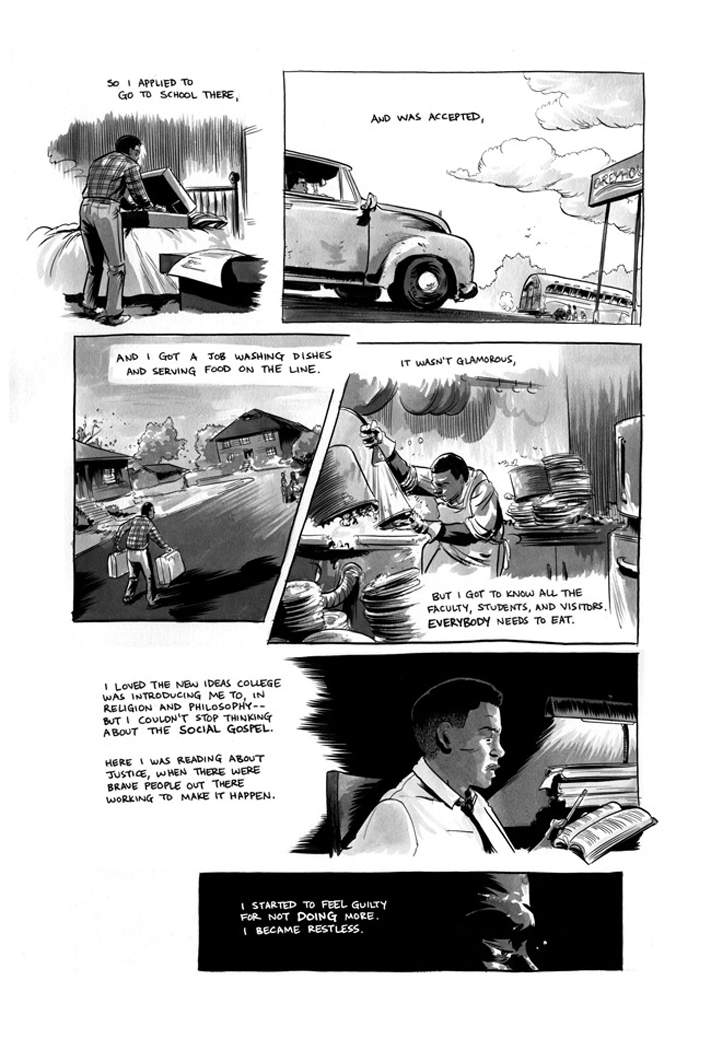

Congressman Lewis was born in 1940 in Pike County, Alabama. His sharecropper parents owned their own farm, enjoying a basically stable life, though living with constant fear under the repressive and demeaning Jim Crow laws of the region.

They laid low; making no waves, fearing the very real and brutal reprisals that could be visited upon them should they dare to transgress the social order. Their son, however, was different. From an early age Lewis carried an activist spark within, fomenting relationships with the chickens on his parent’s farm, caring for them as individuals, eventually “seriously protesting” his parents treatment of the birds as fodder for the dinner table. He would even gather the birds around so that he could preach sermons to the flock. As he grew older his defiant streak leaped to the fore; when told he had to stay home from school in order to work on the farm during harvesting and planting season, Lewis would sneak away to school anyway, instinctively knowing that education meant everything. He was physically unable to sacrifice his future.

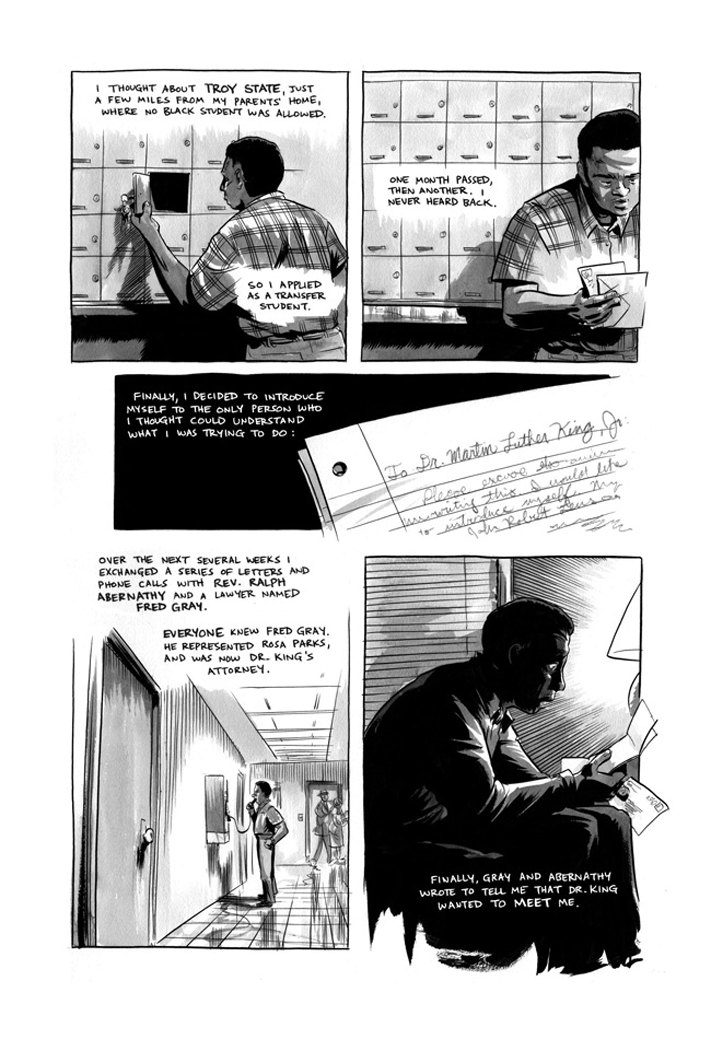

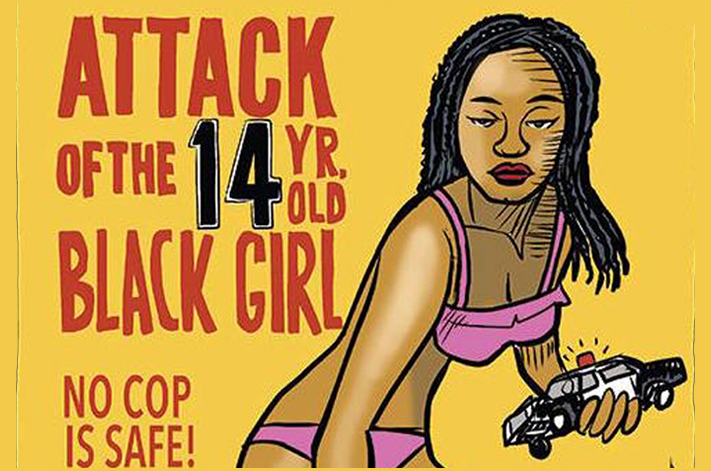

These early details beautifully inform his reaction to the events described in the rest of Book One. Young Lewis couldn’t help but notice the social inequities of the time (the mid-1950s), including the well-appointed schoolhouse facilities for white children contrasted with the bare bones accommodations for blacks. He eventually hears Martin Luther King sermonizing on the radio, which strengthens his activist resolve “like a bolt of lightning.” Further events, both terrible and triumphant, including the brutal murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till (for the crime of saying “Bye, baby” to a white woman in a store), and the yearlong, successful bus boycotts in Montgomery, Alabama, compel Lewis to begin intensive training for civil rights activism. The first focus for the group Lewis joined was to end the segregation of blacks and whites at lunch counters in Nashville Tennessee, blacks being prohibited from being served at all. The resultant lunch counter sit-ins and mass arrests concluded with a victory for desegregation: on May 10th 1960, six downtown Nashville department stores served food to black people for the first time in history. Lewis concludes Book One here.

Walk through a gallery of John Lewis’ work…Civil Rights Icon Makes a Comic of His Own

Factual historical comics are often produced with professionally rendered but characterless drawings. Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story itself, though certainly important as an inspiration to Lewis and other activists of the civil rights era, featured technically proficient but generic art, devoid of personality, the message itself obviously being more important than the (comics) medium. Nate Powell’s expressionistic realism in March is anything but ordinary. As in his very fine 2009 graphic novel Swallow Me Whole, his art has a sweeping dynamism, effortlessly drawing the reader into the story. His scene-setting panels, in particular, are smooth and vibrant. The book’s opening, set in 2009 on the morning of President Obama’s inauguration, features a lovely, very cinematic tracking shot as the artist’s eye roams from a silent pre-dawn street in Washington, D.C. to Lewis’s well-appointed brownstone and its interiors, finally resting on the sleeping congressman upstairs. Powell intuitively captures all of the drama inherent in the congressman’s gripping, ultimately moving story. Teaming him with Lewis and Aydin has resulted in one of the must-read graphic novels of 2013 (and beyond). If I were King of the World I’d certainly put March on Required Reading lists in middle and high schools everywhere. Here’s hoping Books Two and Three appear soon.

Read Related John Lewis’ Moving Graphic Novel Brings the Civil Rights Struggle to a New Generation