Project Description

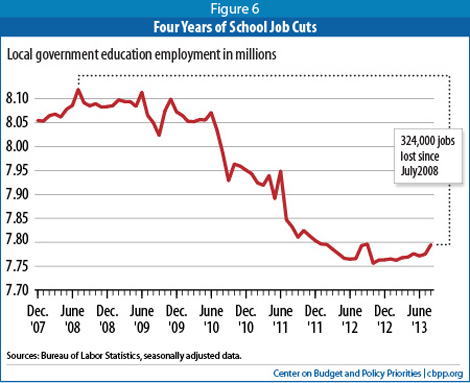

By Michael Leachman and Chris Mai RELATED AREAS OF RESEARCH Our review of state budget documents finds that: Restoring school funding should be an urgent priority. The steep state-level K-12 spending cuts of the last several years have serious consequences for the nation. As of August 2013, local school districts had cut a total of 324,000 jobs since 2008.[4] These job losses have reduced the purchasing power of workers’ families, in turn reducing overall economic consumption, and thus deepened the recession and slowed the pace of recovery. States Have Cut K-12 Schools’ Primary Funding Source States typically distribute most of this funding through formulas that allocate money to school districts. Each state uses its own formula. Many states, for instance target at least some funds to districts that have higher levels of student need (e.g., more students from low-income families) and less ability to raise funds from local property taxes and other local revenues, although this targeting typically is insufficient to fully equalize educational expenditures across wealthy and poor school districts.[5] In addition to the funding they distribute through general aid formulas, states may or may not use separate allocations to fund items such as pupil transportation, contributions to school employee pension plans, and teacher training. Those allocations typically are smaller than general aid funding. For 48 states, the necessary data are available to compare this year’s allocations for the first category of funding, general formula funding with funding before the recession hit.[6] The 48 states included in this analysis are home to 97 percent of the nation’s schoolchildren.

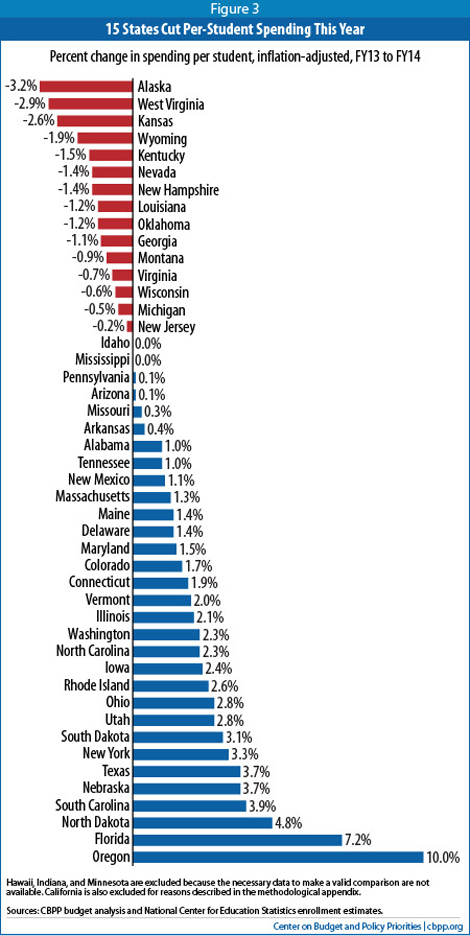

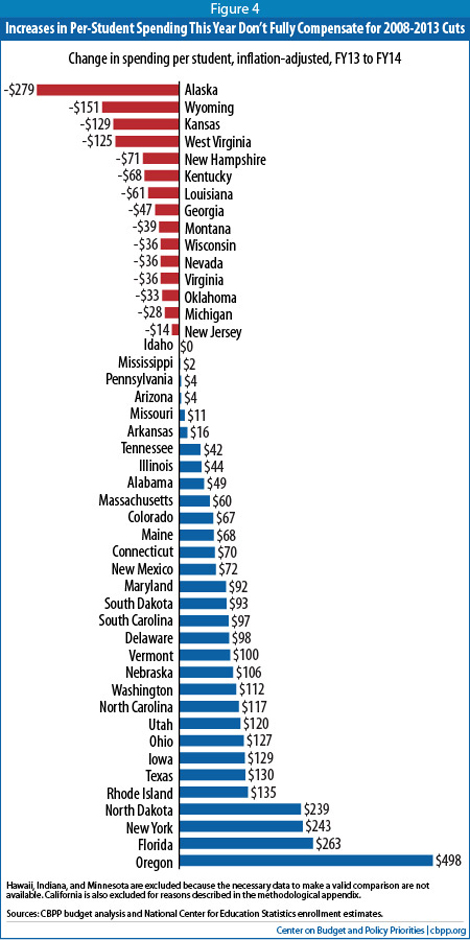

State K-12 Funding in the Current 2013-14 School Year Compared With 2007-08 School Funding in 2013-14 Compared With 2012-13 In 15 states, per-student funding is lower in the current fiscal year (2014), than it was in the last fiscal year (2013), after adjusting for inflation. Other states increased funding for the current school year, but per-pupil spending generally remains far below pre-recession levels. For example, New Mexico’s $72 per-pupil increase this year was not nearly enough to offset the state’s $946 per-pupil cut over the previous five years. Maine increased per-pupil funding by $68 in fiscal year 2014, an increase that pales in comparison to the $465 cut the state made between fiscal years 2008 and 2013. State revenues are starting to improve across the country. State tax revenues grew 8.9 percent in the 12-month period ending in March 2013. But they remain 2.8 percent below 2008 levels after adjusting for inflation. K-12 Education Cuts Have Serious Consequences Local School Districts Hard Pressed to Make Up for Lost State Funding Beyond increasing local revenues, school districts’ options for preserving investments in education services are very limited. Some localities could divert funds from other local services to shore up school district budgets, but this would sustain education spending at the expense of other critical services like police and fire protection. Undermining Education Reform State education cuts are counteracting and sometimes undermining reform initiatives that many states are undertaking with the federal government’s encouragement, such as supporting professional development to improve teacher quality, improving interventions for young children to heighten school readiness, and turning around the lowest-achieving schools. Deep cuts in state spending on education can limit or stymie education reform efforts by limiting the funds generally available to improve schools and by terminating specific reform initiatives. Reforms endangered by funding cuts include: Local school districts have eliminated 324,000 jobs nationally since July 2008, federal data show. (See Figure 6.) This decline has been unprecedented; normally, local education employment grows each year to keep pace with an expanding student population. In addition, education spending cuts have cost an unknown but likely large number of additional jobs in the private sector as school districts have canceled or scaled back private-sector purchases and contracts (for instance, purchasing fewer textbooks). These job losses shrink the purchasing power of workers’ families, which in turn affects local businesses and slows recovery. In the long term, the savings from today’s cuts may cost states much more in diminished economic growth. To prosper, businesses require a well-educated workforce. The deep education spending cuts states have enacted will weaken that future workforce by diminishing the quality of elementary and high schools. At a time when the nation is trying to produce workers with the skills to master new technologies and adapt to the complexities of a global economy, large cuts in funding for basic education undermine a crucial building block for future prosperity. Appendix: Methodology The education funding totals presented in this paper reflect the funding distributed through states’ major education funding formulas. The numbers do not include any local property tax revenue or any other source of local funding. Additional adjustments were made to reflect the following state-specific policies or data limitations: End notes:

September 12, 2013

Some 44 percent of total education spending in the United States comes from state funds (the share varies by state).[2] Cuts at the state level mean that local school districts have to either scale back the educational services they provide, raise more local tax revenue to cover the gap, or both.

K-12 schools in every state rely heavily on state aid. On average, some 44 percent of total education expenditures in the United States come from state funds; the share varies by state.

‘

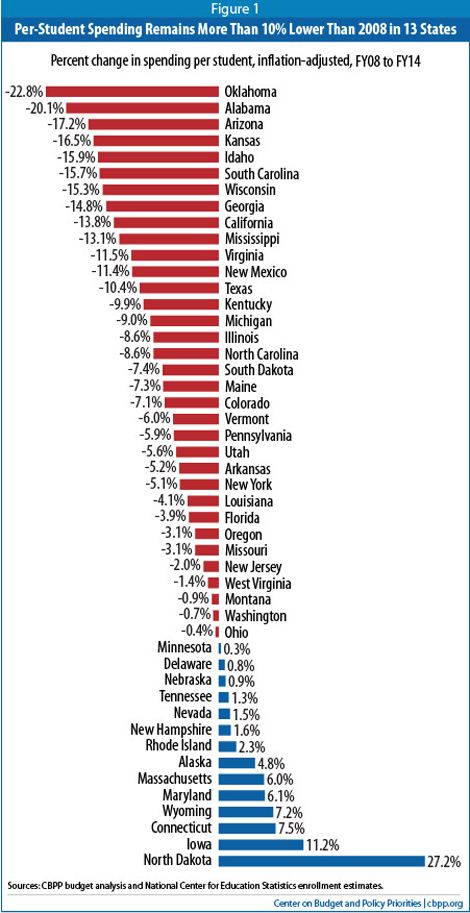

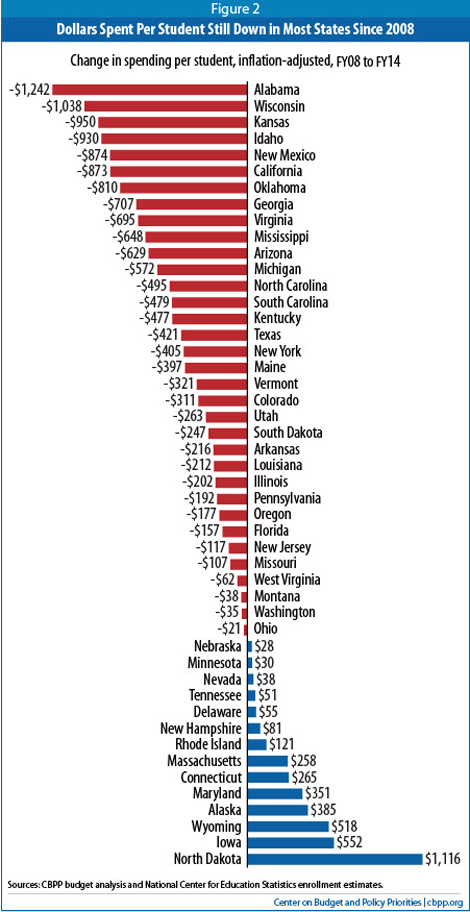

States made widespread and very deep cuts to education formula funding since the start of the recession, and those cuts linger in most states. (See Figures 1 and 2.) This survey finds that, after adjusting for inflation:

Some states continued to cut their per-pupil school funding in the last year. These cuts generally have been modest, but they generally come on top of severe cuts in previous years, leaving state funding for schools far behind pre-recession levels. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

States cut funding for K-12 education — and a range of other areas of spending including higher education, health care, and human services — as a result of the 2007-09 recession, which caused state revenue to fall sharply. Emergency fiscal aid from the federal government initially helped prevent even deeper cuts but it ran out before the economy had recovered, and states have disproportionately chosen to address their budget shortfalls through spending reductions rather than a more balanced mix of service cuts and revenue increases. Cuts are particularly deep when inflation and other cost pressures are considered.

States’ large cuts in education spending have serious consequences for the economy, in both the short and long term. Local school districts typically have little ability to make up for lost state funding on their own. As a result, deep state funding cuts lead to job losses, slowing the economy’s recovery from the recession. Such cuts also counteract and sometimes undermine important state education reform initiatives at a time when producing workers with high-level technical and analytical skills is increasingly important to a country’s prosperity.

The precipitous decline in property values since the start of the recession, coupled with the political or legal difficulties in many localities of raising property taxes, make raising significant additional revenue through the property tax very difficult for school districts. Indeed, property tax collections were 2.1 percent lower in the 12-month period ending in March 2013 than in the previous 12 months, after adjusting for inflation.[/fusion_builder_column]

State education budget cuts prolonged the recession and have slowed the pace of economic recovery by reducing overall economic activity. The spending cuts have caused school districts to lay off teachers and other employees, reduce pay for the education workers who remain, and cancel contracts with suppliers and other businesses. These steps remove consumer demand from the economy, which in turn discourages businesses from making new investments and hiring.