Project Description

Photographic Credit; Students at a New Orleans charter school in 2011. By Ted JacksonTimes Picayune.

The History of Public Education in New Orleans Still Matters

The history of public education in New Orleans still matters (if you want to learn about the malignant legacy of white supremacy.)

'The most formidable obstacle to historical knowledge is the pretentious mania of considering as resolved historical questions which are barely understood and left unexplored because one imagines to have the answers.' ~ Guy Frégault1

Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uno.edu/hist_facpubs Part of the Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons

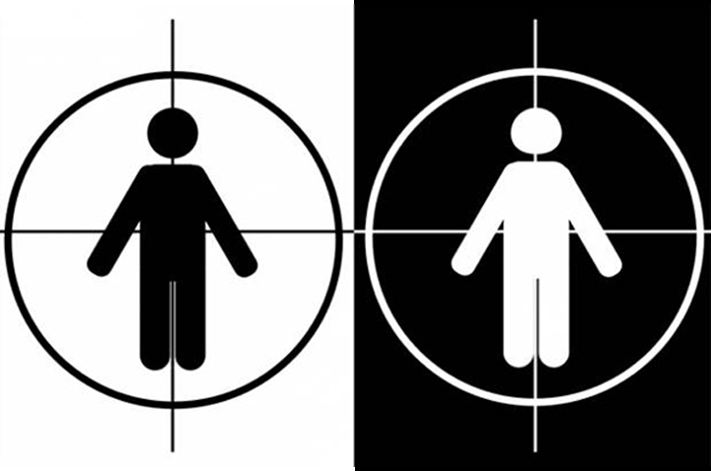

If we cannot see white supremacy in the past, how will we recognize it in 2016?

One could reasonably conclude that, prior to 2005, public education in New Orleans had no history—at least in the minds of the post-Katrina reformers. In a 2015 op-ed column in The New Orleans Advocate celebrating what they felt was the unparalleled success of public charter-school education in New Orleans, the authors boast that the dramatic improvements started with a city that represented “a blank sheet of paper,” and from there, eager reformers developed “a system of schools unlike anything else in the country.”

Ten years after the flood waters from negligently constructed federal levees inundated the city, the reformers have unhitched their narrative from the pre-Katrina history of New Orleans. “[I]t might be easy to forget just how groundbreaking all of this really is,” they boast of their brief history.2 In other words, nothing that came before could be as awesome as we are right now.

Calling attention to another example of historical amnesia, Kristen Buras, in her recent book, Charter Schools, Race, and Urban Space: Where the Market Meets Grassroots Resistance, cites Lessons Learned, 2004-2010, a report by writers from Public Impact and New Schools for New Orleans. In the two paragraphs allotted to the section “History: Pre-Katrina New Orleans,” the authors ignore 164 years of public school history, mentioning only “failing schools” and other deficiencies in their effort to justify the “state takeover of New Orleans schools after the storm.”3

Photographic Credit; Cross Guard Karen Morris, affectionately called Ms. Peaches by the students, stops traffic on S. Carrolton at Birch St. Wednesday, August 24, 2005 at the end of the school day for Ronald E. McNair Elementary School uptown. This was five days before Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans and history was rewritten. By Staff Photo Jennifer Zdon. Times Picayune

Reformers cleverly placed the blame for the failing schools squarely on the backs of the teachers–and their union. History shows this to be an effective strategy when attempting to dismantle the public schools. Katrina presented the opportunity, and mass firings in November 2005 deprived New Orleans of the talents of approximately 7500 New Orleans public school teachers and other employees—“most of them African American.” Under the cover of reform, and in the midst of the horrible uncertainty of post Katrina New Orleans, the classroom veterans were stripped of their livelihoods and their health insurance.4 An immoral action became the foundation of reform.

It was more than a loss of personnel; it was a lobotomy of sorts. The veteran teachers were the living memory of the schools; yet, somehow they had been cast as scapegoats for decades and decades of neglect. Never mind that, as Buras writes, “one undeniable fact” is that “white supremacy, not black deficiencies, accounts for the challenging conditions of black public schools in New Orleans.”5 The reformers do not mention the names of those who came before, nor do they mention past accomplishments. They don’t know the history. For the popular and oft-repeated post-Katrina narrative to be persuasive, there can be no mention of the consequences of white supremacy – only the perceived failure of veteran teachers.

Veteran teacher Billie Dolce was fired along with more than 7,000 other employees of the New Orleans’ public school system in the months after Hurricane Katrina. She never returned to the classroom. ~ Edmund Fountain for Education Week

References to race don’t get much traction these days. Charges that race might play a role in any issue are brushed aside. It is so much easier for the white majority to pretend the accusations have no basis. In “Black Americans, white Americans and the politics of memory,” Times-Picayune columnist Jarvis DeBerry notes that “Black Americans are expected to remember the heroism of the American Revolutionaries and the eloquence of the Declaration of Independence, but forget the slavery that endured after the Revolutionary War and the Constitution.” They are told, DeBerry writes, “to get over it.”6 When it comes to historical inequities in the schools, Black Americans are told “to get over it.” Those who speak of racial disparities in the public schools in present-day New Orleans are told “to get over it, ” or, worse, ignored.

When it comes to historical inequities in the schools, Black Americans are told “to get over it.” Those who speak of racial disparities in the public schools in present-day New Orleans are told “to get over it, ” or, worse, ignored

Perhaps the reference to the “blank sheet of paper” makes more sense as an effort to paper-over a long and painful history, and it helps to block from memory the efforts of determined individuals who spent their underpaid educational careers working against incredible odds to educate all children in the public schools. To ignore the history of racism is to ignore the enormous weight against which dedicated educators have pulled and strained for decades.

With the teachers having been disposed of following the flood, careless and clumsy contracted clean-up crews moved through public school buildings, entering the dry second and third floors and recklessly throwing away old correspondence, historic photographs, paintings of the people after whom the schools were named, scrapbooks of school histories, yearbooks, and so much more. The community’s past became landfill debris.

Before There Was an Effort to Forget

Before there was an effort to forget, and long before reformers fantasized that New Orleans was a blank sheet of paper upon which to write a dazzling new narrative, Joshua Baldwin, one of New Orleans’ education pioneers, expressed regret in 1844 that the guidance from the past for which he searched, had been annihilated. “At the beginning of our educational efforts in 1842,” he wrote, “we were compelled to grope along, but with little light from the past.”

Baldwin went on to explain:

Public Education in New Orleans, 1841-1991. They concluded the first public schools in New Orleans “inaugurated public schools not only in the city but also throughout Louisiana and much of the Deep South.”8

Time has marched on since Crescent City Schools was published in 1991, but DeVore and Logsdon’s simple declaration remains unchanged: “The problems of race are…deeply rooted in the public schools of New Orleans.”9 The imagined blank sheet of paper upon which a new history is being written does very little to separate the racial past from the racial present.

Issues of Class and Race

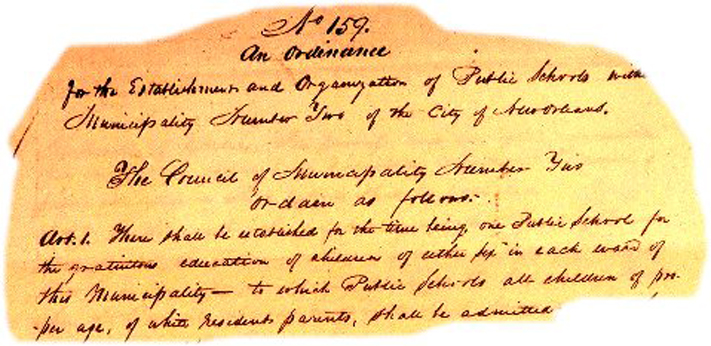

Right out of the gate, race became an issue in how the Crescent City would instruct its children. The “birth certificate” of the city’s public schools, Ordinance No. 159, which authorized public schools in the Second Municipality of New Orleans, was signed by Mayor William Freret on March 26, 1841. The ordinance started a movement to set up and fund public schools across New Orleans’ other municipalities. 10 Historian William Preston Vaughn noted that “New Orleans outshone all antebellum Southern cities with respect to schools and gave Louisiana its good reputation in education.”11

The bad news is that the ordinance, in the very first paragraph, stressed that the schools were limited to “all children of proper age, of white resident parents.”12

The “birth certificate” of the city’s public schools, Ordinance No. 159. New Orleans Public Library

Excluding black children from the first public schools in 1841 was merely a reminder of Act 154, Sec. III, approved by the state legislature on March 16, 1830, stating “[t]hat all persons who shall teach, or permit or cause to be taught, any slave in this State, to read or write, shall, on conviction…be imprisoned not less than one month nor more than twelve months.”13 New Orleans was serious about keeping the enslaved “shackle[d] … with ignorance.”14

New Orleans’ sizeable population of Free People of Color, estimated to be about 20% of the city’s residents, paid taxes to support public schools that were closed to them. According to historian Charles Barthelemy Rousseve, some had sufficient wealth to send their male children to France, “where they might secure an education more thorough than could be had for a long while in New Orleans.”15 In addition, state DeVore and Logsdon, “[t]he free black community…organized its own schools.”16

Before General Benjamin Butler’s forces occupied New Orleans a little over a year after the Civil War began, “no single black child had ever been allowed to enter a free, public school room in New Orleans.” Through the Freedman Schools, the U.S. Army first opened the public school doors to those recently released from cruel bondage. 17

The bad news is that the ordinance, in the very first paragraph, stressed that the schools were limited to 'all children of proper age, of white resident parents.'12

After the Civil War, Louisiana politicians and business leaders used every legal and extra- legal means (violence) to keep the schools as white as possible—a focus that ultimately shortchanged both white and black students. The city leaders, with the active support of the white population, prohibited, then obstructed, then delayed allowing children of Freedmen to attend the schools. Perhaps what frightened them the most was that the children could learn.

On November 15, 1867, military officials turned over to the Board of School Directors of the City of New Orleans twelve Freedmen’s Bureau schools with 560 pupils. Five months later, on April 1, 1868, public school superintendent William O. Rogers reported 3800 “colored” children in the schools. “The attendance of this class of pupils is good,” Rogers wrote. “They are well behaved and are making good progress in a knowledge of the elementary principles of education.” This from a man who would later resign rather than oversee integrated schools.18

The Too-Successful Experiment

New Orleans integrated its public schools during Reconstruction. “Alone in the South,” writes DeVore and Logsdon, and almost singularly in the nation, the public schools of New Orleans reached for the most difficult objective embodied in the American common school ideal: fundamental racial integration—with black and white students, black and white teachers, and black and white administrators.19

This was relatively new ground in the late 1860s, Vaughn points out, because “racially integrated schools were not common in the North at this time.”20

By 1870, “the assertiveness of the black creole families” working with sympathetic legislators enforced the laws passed by radical Republicans to integrate the schools.

Superintendent William O. Rogers had already decided how he would show his repugnance for the plan to mix the races in the schools: He resigned his post. His absence accounts, in part, for the gap in the records in one volume of Orleans Parish School Board correspondence and minutes, April 2, 1870, to July 23, 1877. Explaining his decision in 1877, Rogers said he retired from the Superintendency 7 years ago when the radical authorities assumed control. Their management, or mismanagement, has been one of mixing everything, race & sex included. I am opposed to both mixtures….Our Board has already indicated its policy in the matter of color line and has resolved that hereafter there shall be separate schools for whites and blacks. The decision in my judgment is based upon sound educational ground, irrespective of political or other causes.21

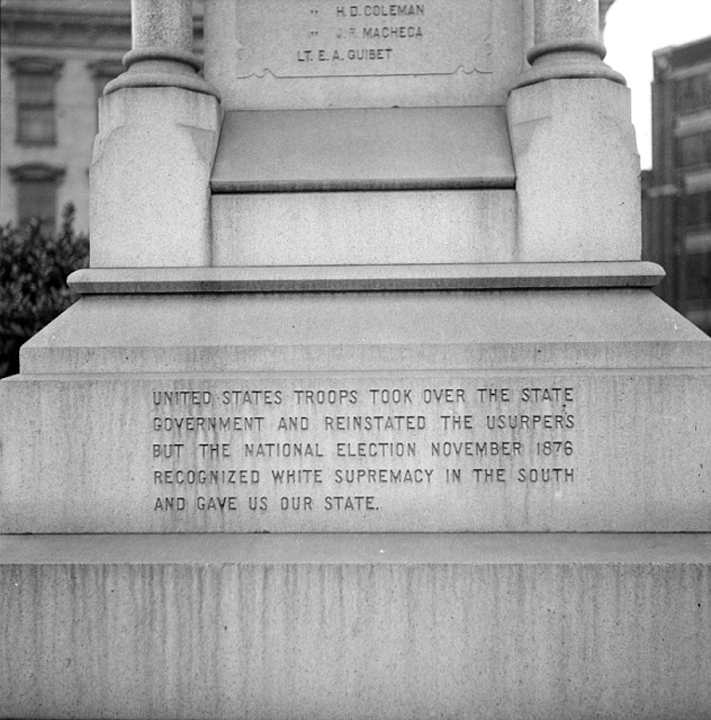

Between 1871 and 1874, a grudging tolerance for mixed schools came about because of short-lived Reconstruction-era efforts to court black votes. The return of anti-integration efforts following the infamous Battle of Liberty Place sparked the “New Orleans school riots” in December 1874. Members of the White League promoted “well-orchestrated violence,” and for a full week, the high school students who followed the White League vandalized integrated schools, terrorized teachers, and “removed suspected black students” from the buildings.22

Photographic Credit; Between 1871 and 1874, a grudging tolerance for mixed schools came about because of short-lived Reconstruction-era efforts to court black votes. Members of the White League promoted and memorialized “well-orchestrated violence.” [To see the full monument in all its grandeur click on the image to enlarge]

White historians whitewashed the narrative of the New Orleans school riots. In The Story of Public Education in Louisiana, Louisiana’s superintendent for public schools, T. H. Harris, declared: “with the committee of boys.”23 In retelling the story, T. H. Harris created his own white reality; however, a school maintenance report presented at a meeting of the Orleans Parish School Board on April 7, 1875, lists the repairs necessary after the White League-inspired boys had done their work. Some schools had as many as 57 broken window panes needing to be replaced as well as needing other repairs.24

DeVore and Logsdon found evidence that approximately one-third of the city’s public schools were integrated between 1870 and 1877, and “the integrated schools were judged the best in the system.”25

Regarding the quality of the teaching faculty in the integrated schools, the Weekly Louisianian, in an 1875 editorial, weighed in on the controversy surrounding the hiring of E.J. Edmunds as a mathematics teacher at the Boys High School. The newspaper noted the criticism of Edmunds, a New Orleanian who had been “liberally educated in France,” and who ranked fifth in a class of more than 200 students at the “Polytechnic, scientific school in Paris.”26

It is tragic that the bold experiment in desegregated schools during Reconstruction was not allowed to continue: it would have made integration a non-issue in the 1960s. “It was not educational failure that eventually ended the daring experiment in New Orleans,” concluded DeVore and Logsdon. 27

The Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction and extinguished the dream of equal education, cementing white supremacy in the South. Federal protections for Freedmen vanished, and power returned to “the old slaveholding class” in Louisiana.28

Archibald Mitchell, one of the “originators” or founders of the Crescent City White League, described by DeVore and Logsdon as a “terrorist, paramilitary” organization that used violence and intimidation against supporters of integration, would go on to serve on the Orleans Parish School Board, 1877-1880. 29

Despite several eyewitness accounts written by Picayune reporter George Washington Cable, who actually visited the integrated schools, Archibald Mitchell, from his seat on the post- Reconstruction School Board, entered his own version of events in the School Board records. He stated with absolute certainty that “public education has greatly deteriorated since colored and white children were admitted indiscriminately into the same schools.”30 Allowing the historical record to reflect the success of Reconstruction-era integration would pose too great a threat to the myths that supported white supremacy. Mitchell’s comments, which echoed those of his fellow School Board members, helped preserve the myths that buttressed white supremacy and gave a political impetus to rolling back reforms in the education of New Orleans’ African American children. Fabricating failure in the minds of the white population proved useful in maintaining or regaining white political control of the schools.

A Lie Becomes Historical Fact

Historians sympathetic to Archibald Mitchell’s narrative that Reconstruction-era integration failed miserably made sure Mitchell’s story was not challenged by the passage of time. This interpretation, spread by many historians, became the dominant narrative in school books in the early 1900s. The “lost cause” sympathies immersed American school children in a false narrative persisting into the present.

In 1938, the Louisiana State Museum published Carpet-Bag Misrule in Louisiana: The Tragedy of the Reconstruction Era Following the War Between the States. With a sense of pride, the cover of the booklet adds that the story within its pages documents “Louisiana’s Part in Maintaining White Supremacy in the South.” More than 60 years after the New Orleans public schools’ integration experiment ended, the booklet’s authors summed up the condition of public education during that seven-year period (1870-1877). “The school system had been debased, disgraced and despoiled,” they wrote. 31

Historian Eric Foner, one of many contemporary historians debunking the Lost Cause myth, acknowledged that, “Historians have long since rejected this lurid account, although it retains a stubborn hold on the popular imagination.”32

A close look at the Carpet-Bag Misrule publication shows that James J. A. Fortier, President of the Board of Curators of the Louisiana State Museum, edited the booklet and wrote the foreword in which he declared “White Supremacy” to be “a cardinal principle of a wise, stable, and practical government.” Fortier previously served as President of the Orleans Parish School Board from 1922-1926, during which time he stated he would be “unwilling to do anything that would affect the white man’s supremacy.”33 Walter Stern completes Fortier’s statement made at the same meeting, quoting Fortier’s proclamation that he “was ready to deny the negro political equality and if necessary resort to force to do so.” 34

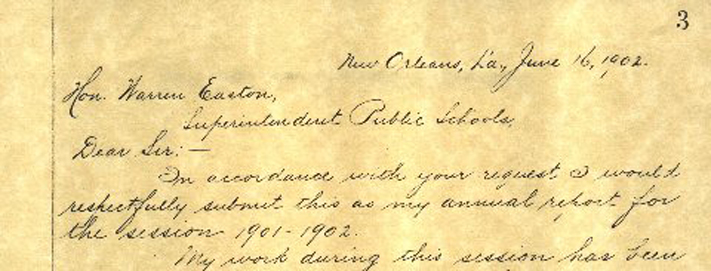

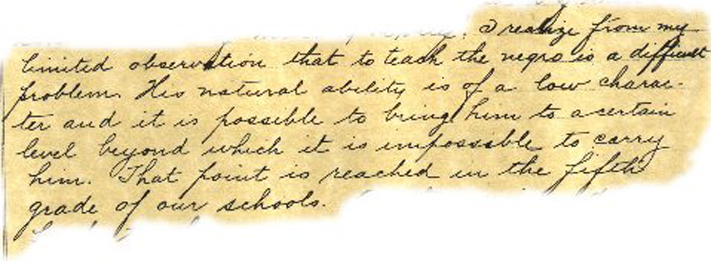

Photographic Credit; In his 1902 annual report to Superintendent Easton, Bauer, after admitting that he only had “limited observation” of the African American schools, went on to declare that “to teach the negro is a difficult problem. [Click on images to enlarge.]

The public schools of New Orleans had another connection to the Carpetbag Misrule booklet in that “Nicholas Bauer, Superintendent, Orleans Parish School Board” also was listed among the museum’s Board of Curators.35 Thirty-six years earlier, Bauer had been an Assistant Superintendent under Superintendent Warren Easton. In his 1902 annual report to Superintendent Easton, Bauer, after admitting that he only had “limited observation” of the African American schools, went on to declare that “to teach the negro is a difficult problem. His natural ability is of a low character and it is possible to bring him to a certain level beyond which it is impossible to carry him. That point is reached in the fifth grade of our schools.”36 The Orleans Parish School Board, in 1923, appointed Bauer Superintendent of the New Orleans Public Schools, and he served until 1940.

White Supremacy and Political Power

White supremacy is a powerful and effective political strategy designed to maintain white control over politics, finance, and education. It perpetuates racial disparities that keep administrations in power, and it is based upon a system of perpetual winners and perpetual losers.

White supremacy is a powerful and effective political strategy designed to maintain white control over politics, finance, and education

In 1908, city leaders were alarmed that proposed new compulsory education laws would require African Americans to get an education. The white supremacists didn’t hide behind racial code words, but were blunt in their assessment: Education posed a threat to the white power structure. The editorial writers of the Daily Picayune warned the white community about the dangers of “making education compulsory in Louisiana.”

It should be remembered that ability to read and write is one of the requirements of admission to suffrage in this State, and inability to comply with it shuts out the great body of the negro vote and a considerable number of whites.

Just as soon as all the negroes in the State shall be able to read and write they will become qualified to vote, and it is not to be doubted that they will demand their rights…with the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Constitution to back them up. Then there will be negro majorities in a great number of the parishes and wards of the State with no legal means of neutralizing or defeating that most dangerous situation.37

Controlling who had access to public education enabled political leaders to control the elections, thereby safeguarding and perpetuating white supremacy through the ballot box. The inequitable system trapped generations of the city’s population in poverty, and it denied them the education that would have lifted them out of poverty.

Because education was not a priority in Louisiana, the education budget ran chronically short of meeting the needs of the state’s students. Paying African American teachers less than their white counterparts was one more way to save money–and reinforce the social status quo.

Withholding funding for school buildings for African American students provided another way to save money and, at the same time, remind the little children they were of little importance in the grand scheme of things. In 1927, O.C. W. Taylor, a former public school teaching veteran who helped co-found the Louisiana Weekly, investigated and wrote a series of articles about the public schools serving African American children. He noted that there were 2700 students jammed into the Thomy Lafon Elementary School (Sixth and South Robertson Streets), calling it “the largest elementary Negro school in the world.”38

Throughout the state, funds for the “Negro schools were being diverted to other uses.”

The next year, the Louisiana Weekly published an editorial reminding the Orleans Parish School Board it had promised to stop building wood-frame school buildings because they were a “fire hazard”; yet, the Weekly cited three instances of new wood-frame buildings built for African American students.39 Five years later, in 1933, the Louisiana Weekly again reminded an uncaring city in a headline: “Investigation Conducted by Louisiana Weekly reveals Crowded School Conditions.”40

In 1938, Louisiana’s State Superintendent of Education, T. H. Harris, gave an unusually candid address that was quoted in the New Orleans Item. He admitted there was “no serious intention in most of the parishes to provide school facilities for Negro children,” and there was no “serious concern” about the matter. State governments let local governments decide how to divide the funding between white and black students. “[T]he result in some cases, was no division at all,” states William Ivy Hair.41 Throughout the state, funds for the “Negro schools were being diverted to other uses.”42 It is fortunate for Louisiana that the Julius Rosenwald Fund contributed money to help build 442 schools serving African American children across Louisiana.43 In addition, by 1950, there was an “extensive black parochial system” in New Orleans, providing limited educational opportunities to the city’s large Catholic African American population.44

Reminders of the racial order could be found almost everywhere. Even the annual directories of the public schools carefully separated the listings of the “White” schools and the “White” faculty—always placed in the first section of the booklets, from the “Colored” schools and staff—always in the back.45

More Challenges to the Established Order

Still to come were the turbulent days surrounding the integration of the city’s public schools, which previous School Boards had punted down the road. For decades before the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision in 1954, African American educators and community leaders, such as Reverend Henderson Dunn, Dr. Joseph Hardin, Sylvanie F. Williams, and O.C.W. Taylor, fought Jim Crows laws by demanding equal educational and recreational opportunities, decent school buildings, and adequate funding. 46

Even the annual directories of the public schools carefully separated the listings of the 'White' schools and the 'White' faculty—always placed in the first section of the booklets, from the 'Colored' schools and staff—always in the back.45

Relying on the tireless legal strategies of A. P. Tureaud, a new generation of fearless parents stepped up and, despite the hostile mobs that formed in 1960, made sure that first- graders Leona Tate, Tessie Prevost, Gail Etienne, and Ruby Bridges were able to enter McDonogh 19 and Frantz elementary schools. This embarrassingly minimal effort to desegregate the schools would drag on for years as political leaders looked the other way, the School Board dragged its feet, and the community maintained its opposition.

The racially-charged issue continued into the 1970s as the school system was forced to integrate the teaching staffs in the schools. Mark Cortez contends the Orleans Parish School Board “did as little as possible, just enough to give the appearance of positive action and keep the courts out of local integration.”47 In the 1960s, following the deliberately slow process of student integration, the percentage of white students in the city’s public schools decreased only 5.9%. However, in the 1970s, after faculty desegregation, white enrollment plunged by 62.9%. 48 The dramatic loss of white support for public education and the decrease in the city’s white population did not stop the teachers, principals, and administrators who kept open the public schools for the benefit of the community.

In a movement in the late 1980s, protests ramped up at School Board meetings and other venues to remove the names of slave traders, “slave masters and Confederate figures at more than 40 schools, most of which [had] predominantly black student enrollments.” The protests were led by Carl Galmon, president of the Louisiana State Committee Against Apartheid, and Malcolm Suber, a community leader and activist.49 Their goal was not only to remove selected names from the pedestals of public honor, but expose the brutality and cruelty of the individuals for all to see. The School Board finally approved a “name-change” policy on January 21, 1993.50

The horror had been stripped by adding “good” or “kind” before “slave owner,” harkening back to an imagined time featuring caring masters and contented slaves. Myths, no matter how absurd, are hard to dispel.

The names of some prominent enslavers and Confederate leaders came down from the buildings, and children learned about new role models who looked like them and who succeeded in spite of an oppressive national system.

Many mocked the school-name-change victory as meaningless in the face of what they considered to be much larger and more pressing educational issues– evidence that few at the time were able to make the connection between white supremacy and lingering poverty.51

The School Board’s policy was not popular in a region in which the term “slave owner” had little residual negative historical meaning among the white community. The horror had been stripped by adding “good” or “kind” before “slave owner,” harkening back to an imagined time featuring caring masters and contented slaves. Myths, no matter how absurd, are hard to dispel.

Furthermore, by the time of the public schools’ name-change policy, the horrors of slavery still remained an abstraction for much of the white population. Yet, little by little, a chorus of community residents whose grandparents and great-grandparents remembered their history—residents who had been speaking the truth for years–were finally beginning to be heard. Many teachers in the schools had heard these oral history narratives from family members but had never seen them in the textbooks they used.

More historians and policy makers began to acknowledge the horrific details of the brutal slavery system that shattered family ties, perpetuated torture, and sexually exploited women and children.52

It is an ironic twist that the post-Katrina school name changes proceeded with almost no community input, and the long-fought-for names of inspiring individuals were quickly replaced with corporate names and logos disconnected from the history and culture of New Orleans.53

Placing a Value on History

The stories dating from the origins of the city’s public schools in 1841 seem only to interfere with the blank-sheet-of-paper narrative, the idea there was nothing here of much consequence before the reformers arrived.

Fannie C. Williams and Eleanor Roosevelt. Photographic Credit; Orleans Parish School Board Collection, Special Collections, Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans

The history of the New Orleans Public Schools shows that when times were at their toughest, teachers stepped up to guide children, comfort them, deal with their personal and family issues, provide desperately needed nutrition during school hours, and offer alternatives to suspension and failure. One vivid example from the past is Fannie C. Williams, who served as principal of Valena C. Jones Elementary School from 1921-1954. She found ways to provide nutritional programs and medical care for her students. She started a wide range of social programs, made sure the students had access to library books through bookmobile visits, and took them on many cultural field trips. Fannie C. Williams was so well-connected that she brought in guests such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary McLeod Bethune to meet the Jones Elementary children.54

The sheer magnitude of the historical obstacles caused by the racial climate of New Orleans, and the tales of teachers, community members, students, and school administrators who worked long and hard to combat racism, should not be lost. To list the names of George Longe, Minnie Finley, Charles Kilbert, Maude Dedeaux Crocker, Yvonne Busch, Lawrence Crocker, Dr. Joseph Davis, Duncan Waters, Vorice Waters, Charles J. Hatfield, Felix James, Anna B. Henry, and Myrtle Banks barely scratches the surface. It should be evident to anyone with knowledge of the New Orleans public schools–or experience working within them, that New Orleans boasts countless educators who deserve their place in history.

History shows that white supremacy kept creative children in inferior schools so that white people could blame the black population for inferior schools – a self-fulfilling white prophecy. Cortez sums it up: “white parents were aware of the deprivation that black schools suffered in the past and, therefore, concluded that these schools had substandard educational programs.”55 This racially charged view of public schools survived the federal floods in 2005.

White supremacy impaired the community in other ways. The white community seemed unable to comprehend the love and the strength of the teachers who believed in the children. They had no understanding of the spirit that fostered intellectual life in crumbling structures.

It is an ironic twist that the post-Katrina school name changes proceeded with almost no community input, and the long-fought-for names of inspiring individuals were quickly replaced with corporate names and logos disconnected from the history and culture of New Orleans.53

Monica White found ample evidence of teachers and principals who “sought to create academic excellence in their teaching of African American children of New Orleans.”56 She noted that “the African American community and family pulled together to supplement the meager educational resources and materials provided by the state.”57

Instead of acknowledging the oppression of white supremacy and learning from past mistakes and successes, we now pretend there was nothing but a wasteland prior to the arrival of the reformers. A knowledge of history has been replaced by the new arrogance. The new arrivals stripped from the historical record the narrative of the time before they arrived. In place of the long and complex story, they substituted one word: “failure.”

When history is viewed as an impediment, an annoyance, or worse, as nonessential, it severs the continuity between past and present. And, it undermines our ability to assess the root causes of the problems confronted by teachers and students in the city’s public schools.

In a 2013 study cited by researcher Kristen Buras, a young woman summarized what she experienced as a new teacher in post-Katrina New Orleans. According to Buras, “She described education reform in New Orleans…as an act of white supremacy and historical annihilation.”58

When the elevator opens

Sometimes an elevator can be an unexpected portal to history.

In 1985, The Orleans Parish School Board appointed Dr. Everett Williams the first African American Superintendent of the New Orleans Public Schools. In May 1992, friends of Dr. Williams gathered in a downtown New Orleans hotel to celebrate the Superintendent’s retirement.

It was a surreal scene because, on the same evening in the same downtown hotel, men and women devoted to the Confederacy and the “Lost Cause” were holding their formal ball. It was an odd sight as impeccably-dressed friends of Dr. Williams shared the elevators with men in Confederate uniforms and women dressed as Southern Belles.

On the floor below Dr. Williams’ retirement party, the elevator opened to a scene from the Old South–even a Confederate flag was on prominent display. The past disappeared as quickly as the elevator door closed, and when it re-opened, guests witnessed a gathering celebrating the successful conclusion of the remarkable educational career of the first African American to be appointed to the public schools’ top position.

It took 150 years to get to this party in which the elevator served as a time machine. Throughout that evening, the elevator door might open on the remembrance of the war to keep black people in chains, or it might open on the ongoing struggle to leave slavery in the past. That ironic moment should be remembered because it suggests what might be below the imagined blank sheet of paper upon which the new post-Katrina schools were developed.

History shows that white supremacy kept creative children in inferior schools so that white people could blame the black population for inferior schools – a self-fulfilling white prophecy

There is a danger in ignoring, forgetting, or remaining ignorant of the past. The various leaders of the various acronyms that spell out post-Katrina education in New Orleans would do well to pay attention to Sarah Bond’s caution about papering over the years that came before.

“Instead of establishing a clean slate,” she states, “it may well serve to perpetuate the mistakes of the past.”59

One of those mistakes is to ignore the malignant legacy of white supremacy.

Al Kennedy

Feb. 12, 2016

There is a danger in ignoring, forgetting, or remaining ignorant of the past.

Kennedy’s areas of focus have shed light on the history of local public schools, the musical heritage of New Orleans, and the Mardi Gras Indians. His previous book, Chord Changes on the Chalkboard: How Public School Teachers Shaped Jazz and the Music of New Orleans, received numerous awards, including the Jazztown Award, the Henry Kmen Award, the New Orleans International Music Colloquium Jazz Supporter Award, and the Mardi Gras Indian Hall of Fame Blue Eagle Award. Kennedy was included among notable Louisiana and national writers at the 2003 Louisiana Book Festival.

Kennedy earned a BA from Loyola University, followed by a masters degree in public administration and a PhD in urban studies/urban history from the University of New Orleans. He enjoys jazz, photography, and volunteering for the New Orleans Mardi Gras Indian Hall of Fame. Kennedy resides in Metairie, Louisiana, with his family.

2 Dan Cardinali and Sara Massey, “N.O. models formula for school improvement,” The New Orleans Advocate, January 23, 2015, p. B9.

3 Kristen Buras, Charter Schools, Race, and Urban Space: Where the Market Meets Grassroots Resistance (New York: Routledge, 2015), p. 89; Dana Brinson, Lyria Boast, Brian C. Hassel, and Neerav Kingsland, New Orleans-Style Education Reform: A Guide for Cities: Lessons Learned, 2004-2010, (New Orleans: New Schools for New Orleans, 2012), p. 15. Accessed through www.newschoolsforneworleans.org/guide/.

4 Sue Sturgis, “Is justice near for New Orleans teachers wrongly fired after Katrina?” Facing South, The Institute for Southern Studies, August 27, 2014. Accessed through http://www.southernstudies.org/2014/08/is-justice-near-for-new-orleans-teachers-wrongly-f.html

5 Buras, p. 23.

6 Jarvis DeBerry, “Black Americans, white Americans and the politics of memory,” The Times-Picayune, February 13, 2015, p. B7.

7 Annual Reports of the Council of Municipality Number Two, of the City of New Orleans, on the condition of its Public Schools, New Orleans, 1845, p. 34, Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton memorial Library, Tulane University, New Orleans, La.

8 Donald E. DeVore and Joseph Logsdon, Crescent City Schools: Public Education in New Orleans, 1841-1991, (Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, 1991), p. 1.

9 DeVore and Logsdon, p. 3.

10 Robert Meyer Jr., Names Over New Orleans Public Schools, (New Orleans: Namesake Press, 1975), p. 2.

11 William Preston Vaughn, Schools for All: The Blacks & Public Education in the South, 1865-1877, (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1974), p. 50.

12 Ordinance No. 159, Second Municipality Council, Ordinances and Resolutions, No. 1-545, Vol. 4, May 5, 1840 – March 28, 1843, pp 63-64, City Archives, New Orleans Public Library, (AB310, 1836-1852, 2nd Mun, microfilm roll #90-133). For finding aids, see http://www.neworleanspubliclibrary.org/~nopl/inv/neh/nehab.htm#ab26.

13 Act 154, Sec. III, A New Digest of the Statute Laws of the State of Louisiana, From the Change of Government to the year 1841, Inclusive, Compiled by Henry Bullard and Thomas Curry, (New Orleans: E. Johns & Co, Stationers’ Hall, 1842) pp. 271-272, Louisiana and Special Collections, Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans. Available online.

14 DeVore and Logsdon, p. 3.

15 “1855: Free people of color flourished in antebellum New Orleans,” Times Picayune/Nola.com, August 20, 2011, accessed through http://www.nola.com/175years/index.ssf/2011/08/1855_free_people_of_color_flou.html; Charles Barthelemy Rousseve, The Negro in Louisiana: Aspects of His History and His Literature, (New Orleans: Xavier University Press, 1937), reprint issued by the Johnson Reprint Corporation, New York, 1970, p. 43.

16 DeVore and Logsdon, p. 42. The Institution Catholique des Orphelins Indigens, opened in 1848, was funded through a bequest by Marie Couvent, believed to have been born in Africa and who died in 1837. It is significant because, when private contributions dropped during the Civil War, the school appears to have received limited funding in 1862 “to be expended under the supervision of the Bureau of Education and Superintendent of Public Schools.” See: Robert Meyer Jr., Names Over New Orleans Public Schools, (New Orleans: Namesake Press, 1975), p. 47.

17 DeVore and Logsdon, p. 40, 55. By the end of 1864, the military forces under Major General Nathaniel P. Banks had hired 162 teachers to teach 9571 formerly enslaved children and 2000 adults in 95 Freedmen schools in Louisiana. See: John W. Blassingame, The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Spring, 1965), p. 154, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2294350 Accessed: 04-01-2016 17:44 UTC.

18 (51) Orleans Parish School Board Minutes, Fourth District, September 8, 1862 – November 14, 1863; Superintendent’s Office, copies of reports, circulars, correspondence, October 20, 1865- April 2, 1870 and July 23, 1877 – June 1, 1878, p. 284, housed in the Orleans Parish School Board Collection, Special Collections, Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans. William O. Rogers was making his report to Daniel K. Whitaker, Secretary to the Mayor of New Orleans. In Schools for All, p. 87, Vaughn made the following observation: “Ephraim S. Stoddard pointed out in 1874 that New Orleans citizens should not be upset by mixed schools, since the schools had been integrated for years. Before the Civil War, said Stoddard, illegitimate children, fathered by prominent white citizens of their black mistresses, were enrolled in schools as whites ‘and no objections made.’”

19 DeVore and Logsdon, p. 40.

20 Vaughn, p. 55.

21 (51) Orleans Parish School Board, Fourth District, September 8, 1862 – November 14, 1863; Superintendent’s Office, copies of reports, circulars, correspondence, October 20, 1865- April 2, 1870 and July 23, 1877 – June 1, 1878, pp 402-403, Orleans Parish School Board Collection, Louisiana and Special Collections, Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans. Note that summaries of this volume can be found online through: http://cdm16313.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/p15140coll4.

22 DeVore and Logsdon, p. 76; Vaughn, p. 95. 23 Thomas H. (T.H) Harris,

23 Thomas H. (T.H) Harris,

24 Report, Committee on School Houses, Vol 54, Orleans Parish School Board, Minutes, January 9, 1875 – February 7, 1877, Meeting, April 7, 1875, pp 25-27.

25 DeVore and Logsdon, pp. 68, 70.

There was no violence or unseemly conduct on the part of the boys, a fact that was attributable, no doubt, to the influence of General Ogden, who seems to have advised The Story of Public Education In Louisiana, (Baton Rouge, 1924), p. 81, full text available at: http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062728087;view=1up;seq=58. Three months before the mass vandalism of the schools, General Frederic Nash Ogden led the Battle of Liberty Place to restore white supremacy.

26 DeVore and Logsdon, p. 81; “Our Public Schools,” The Weekly Louisianian, September 18, 1875, p. 2. The newspaper went on to describe Edmonds as a French military officer with “some admixture of African or negro blood.” When the critics refused to halt their racist protests, Edmunds stepped forward and issued a public challenge for a unique duel: If someone could best him in a mathematics competition, he would not accept the teaching position. There followed community silence, and he was hired. See “Edmonds challenges city to a duel at the blackboard,” Applause, A Publication of the New Orleans Public Schools, Vol. 12, No. 9, May 1989, p. 3. Applause is archived in the Orleans Parish School Board Collection, Louisiana and Special Collections, Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans. The name also appears as E. J. Edmonds in some newspaper stories.

27 DeVore and Logsdon, p. 76.

28 DeVore and Logsdon, p. 76; Light Townsend Cummins et al., Louisiana: A History, 6th ed., (West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell, 2014), p. 236.

29 Carpet-Bag Misrule in Louisiana: The Tragedy of the Reconstruction Era Following the War Between the States, A Publication of the Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans, LA, September 1, 1938, p. 39; Devore and Logsdon, pp. 76, 358.

30 Orleans Parish School Board Minutes, June 22, 1877, p. 56, OPSB Collection, Louisiana and Special Collections, Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans.

31 Carpet-Bag Misrule, p. 19.

32 Eric Foner, “Why Reconstruction Matters,” The New York Times – Sunday Review, March 28, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/29/opinion/sunday/why-reconstruction-matters.html.

33 Carpet-Bag Misrule, p. 93; DeVore and Logsdon, p.p. 167, 201.

34 Walter Stern, The Negro’s Place: Schools, Race, and the Making of Modern New Orleans, unpublished dissertation, Tulane University (2014), pp. 141, 142.

35 Carpet-Bag Misrule, p. 93.

36 Nicholas Bauer, “Annual Report, 1902,” Notations on Various Schools, 1903-1906, 1909, p. 18, OPSB Collection, Louisiana and Special Collections, Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans.

37 “Compulsory Education and White Supremacy,” The Daily Picayune (Times-Picayune), May 10, 1908, p.

38 O. C. W. Taylor, “The Public School Your Child Attends,” Louisiana Weekly, April 9, 1927, p. 4.

39 “What About Our Schools,” Louisiana Weekly, February 18, 1928, p. 6.

40 “Investigation Conducted by Louisiana Weekly Reveals Crowded School Conditions,” Louisiana Weekly, October 28, 1933, p. 1.

41 William Ivy Hair, Bourbonism and Agrarian Protest: Louisiana Politics, 1877-1900, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969), p. 125, limited access online at: Agrarian Protest: Louisiana Politics

42 “More Negro Schools Asked – Charges of Fund Diversion Assailed at Alliance session,” The New Orleans Item, July 6, 1938, p. 3.

43 The Rosenwald Fund was “a Chicago charity that financed the building of schools for African Americans throughout the South.” See: Wall & Rodrigue, p. 305.

44 John B.

45 See Raphael Cassimere, Jr., “Equalizing Teachers’ Pay in Louisiana,” Education in Louisiana, Vol. XVIII, Michael G. Wade, Ed., The Louisiana Purchase Bicentennial Series in Louisiana History (Lafayette: Louisiana: Center for Louisiana Studies, 1999), pp. 429 – 440.

46 For more names, see DeVore and Logsdon, “Black Schools, 1900-1945,” pp. 179 -215.

Alberts, “Black Catholic Schools: The Josephite Parishes of New Orleans During the Jim Crow Era”. U.S.

Catholic Historian 1994, 12 (1). Catholic University of America Press, p. 97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25154012.

The article explains actions taken by New Orleans’ Catholic African Americans to provide schools for their children who had been excluded from Louisiana’s public schools.

47 Mark Cortez, “The Faculty Integration of New Orleans Public Schools, 1972,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Autumn, 1996), p. 423.

48 Ibid., p. 427. While Cortez explains that overall white flight from New Orleans to the suburbs cannot be explained solely by public school integration, what was going on in the schools was a factor.

49 Rhonda Nabonne, “School Renamed to lose Reminders of Slavery,” Times-Picayune, July 1, 1995. Accessed through The University of New Orleans–On Campus Access to Databases. According to Times-Picayune columnist James Gill, “Nobody ever raised any objections to school names until Galmon came along.” See James Gill, “Spirit of 1811 and School Names,” Times-Picayune, September 18, 1994.

50 Leslie Williams, “New Policy Allows Schools to be Renamed,” Times-Picayune, January 22, 1993. Accessed through The University of New Orleans–On Campus Access to Databases. Leslie Williams notes: “The name-change policy was approved by a 6-1 vote, with Leslie Jacobs opposing it because the policy has no ‘education process.’”

51 Author’s note: When I retired from the Orleans Parish School Board in 1998, I left behind a filing cabinet with several drawers of materials I had collected about the school name changes. The many folders contained news clippings from around the world, letters—both positive and negative– from local and national sources, records of phone calls from national media, and scribbled messages from angry callers. Those materials in my former office at 4300 Almonaster Ave. were lost in the 2005 flood waters.

52 See Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism,” (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

53 In a move that is puzzling and disturbing, the Orleans Parish School Board voted on December 15, 2015, to prohibit the renaming of public schools. See: Danielle Dreilinger, “Orleans Parish School Board affirms: No more school name changes,” The Times-Picayune/NOLA.Com, December 15, 2015, accessible at: http://www.nola.com/education/index.ssf/2015/12/orleans_parish_school_board_af.html.

54 Fannie C. Williams, conversation with the author, ca 1978; “Who was Fannie C. Williams?” Website of the Fannie C. Williams Charter School. Accessed through: http://fcwcs.org/about-fcw-charter/who-was-fannie-c-williams/.

55 Cortez, p. 432.

56 Monica A. White, “Paradise Lost? Teachers’ Perspectives on the Use of Cultural Capital in the Segregated Schools of New Orleans, Louisiana,” The Journal of African American History, Vol. 87 (Spring 2002), p. 270.

57 Ibid., p. 280.

58 Buras, 154,

59 Sarah E. Bond, “Erasing the Face of History,” The New York Times, May 14, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/15/opinion/15bond.html

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license. We thank the Author, Al Kennedy, for his kindness, awareness, research, and for inviting us to look at the ways in which we deny the democratic process to all our people. May we acknowledge the reality that we, the people, reject principles we say we believe in. Might we ever look at our history and chose to act in ways that truly honor our fellow citizens?