Project Description

The Woman Who Beat The Klan

In 1987, my living room could not have been more minimally furnished. A desk. A chair. A wall of books. Only a few items of visual interest sat on the mantel of my fake fireplace. Among them was — horrific image ahead — a postcard of a 19-year-old African American boy. His name was Michael Donald, and he was hanging from a tree limb in Mobile, Alabama.

That postcard had arrived in an audacious request for funds from Morris Dees, founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center. I have no idea why I displayed that photo of Michael Donald’s lynching or why I kept it there — every time I looked at it, I had to turn away. It took me months to realize that the post card was actionable. I was supposed to do something about it.

That summer I went to Alabama to interview Michael Donald’s mother and Morris Dees and anyone who’d talk to me. Gilles Peress, the great Magnum photographer, took pictures of people who scared me so much I interviewed them on the phone. On November 1, 1987, The Woman Who Beat the Klan was the cover story of The New York Times Magazine.

In four decades as a journalist, I never wrote anything as good, as surprising, as important as this piece. Recently, a noble cause wrote me and asked, on the eve of the grand jury announcement in Ferguson, Missouri, if it could republish the piece. What a wise request — the reaction of Michael Donald’s mother is close in spirit to the reaction of Michael Brown’s parents in Ferguson. I doubt that any piece of journalism can affect how Michael Brown’s community will react and how we will feel when the decision is announced, but maybe there is something to be learned from Beulah Mae Donald, who was the first true Christian I ever met.

I’ve updated the piece to say what’s happened to the people since 1987. Apologies for the length. I hope you’ll read all of it — what Mrs. Donald says at the end still makes me cry.

But Beulah Mae Donald knew that she did, and so she woke from her dream at two in the morning in Mobile, Ala., on March 21, 1981. The first thing she did, she later said, was to look in the other bedroom, where her youngest child slept. Michael, 19, wasn’t there. She telephoned one of her six other children. Though Michael had watched television with his cousins earlier in the evening, he had left before midnight.

Mrs. Donald drank two cups of coffee and moved to her couch, where she waited for the new day. At dawn, Michael still wasn’t home. To keep busy, she went outside to rake her small yard. As she worked, a woman delivering insurance policies came by. ”They found a body,” she said, and walked on.

Shortly before 7 A.M., Mrs. Donald’s phone rang. A woman had found Michael’s wallet in a trash bin. Mrs. Donald brightened — Michael was alive, she thought. ”No, baby, they had a party here, and they killed your son,” the caller reported. ”You’d better send somebody over.”

A few blocks away, in a racially mixed neighborhood about a mile from the Mobile police station, Michael Donald’s body was still hanging from a tree. Around his neck was a perfectly tied noose with 13 loops. On a front porch across the street, watching police gather evidence, were members of the United Klans of America, once the largest and, according to civil rights lawyers, the most violent of the Ku Klux Klans.

Less than two hours after finding Michael Donald’s body, Mobile police would interview these Klansmen. Lawmen learned only much later, however, what Bennie Jack Hays, the 64-year-old Titan of the United Klans, was saying as he stood on the porch that morning. ”A pretty sight,” commented Hays, according to a fellow Klansman. ”That’s gonna look good on the news. Gonna look good for the Klan.”

On Friday night, after the jurors announced they couldn’t reach a verdict, the Klansmen got together in a house Bennie Hays owned on Herndon Avenue. According to later testimony from James (Tiger) Knowles, then 17 years old, Tiger produced a borrowed pistol. Henry Francis Hays, Bennie’s 26-year-old son, took out a rope. Then the two got in Henry’s car and went hunting for a black man.

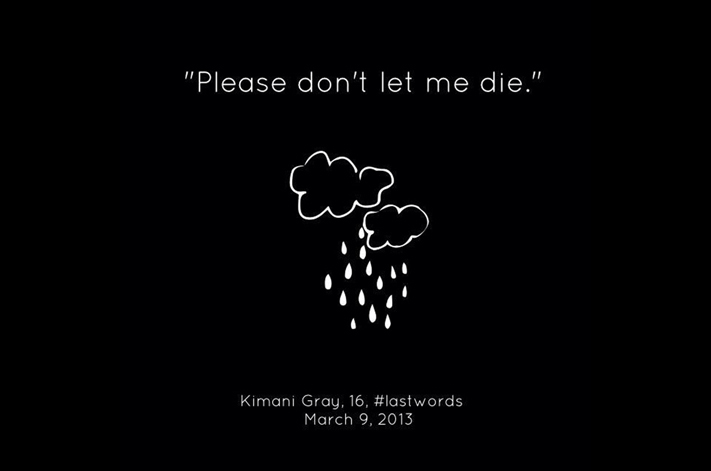

Michael Donald was alone, walking home, when Knowles and Hays spotted him. They pulled over, asked him for directions to a nightclub, then pointed the gun at him and ordered him to get in. They drove to the next county. When they stopped, Michael begged them not to kill him, then tried to escape. Henry Hays and Knowles chased him, caught him, hit him with a tree limb more than a hundred times, and, when he was no longer moving, wrapped the rope around his neck. Henry Hays shoved his boot in Michael’s face and pulled on the rope. For good measure, they cut his throat.

Around the time Mrs. Donald was having her prescient nightmare, Henry Hays and Knowles returned to the party at Bennie Hays’s house, where they showed off their handiwork, and, looping the rope over a camphor tree, raised Michael’s body just high enough so it would swing.

At that point, a grieving mother might have been expected to issue a brief statement of gratitude and regret, and then return to her mourning. Beulah Mae Donald would not settle for that. From the moment she insisted on an open casket for her battered son —”so the world could know” — she challenged the silence of the Klan and the recalcitrance of the criminal justice system. Two convictions weren’t enough for her. She didn’t want revenge. She didn’t want money. All she ever wanted, she says, was to prove that ”Michael did no wrong.”

Mrs. Donald’s determination inspired a handful of lawyers and civil rights advocates, black and white. Early in 1984, Morris Dees, co-founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center, suggested that Mrs. Donald file a civil suit against the members of Unit 900 and the United Klans of America. The killers were, he believed, carrying out an organizational policy set by the group’s Imperial Wizard, Robert Shelton. If Dees could prove in court that this ”theory of agency” applied, Shelton’s Klan would be as liable for the murder as a corporation is for the actions its employees take in the service of business.

Mrs. Donald and her attorney, State Senator Michael A. Figures, agreed to participate in the civil suit. Last February, an all-white jury in Mobile needed to deliberate only four hours before awarding her $7 million. In May, the Klan turned over the deed to its only significant asset, the $225,000 national headquarters building in Tuscaloosa. Meanwhile, Mrs. Donald’s attorney moved to seize the property and garnish the wages of individual defendants. ”The Klan, at this point, is washed up,” says Henry Hays, from his cell on death row.

On the strength of evidence presented at the civil trial, the Mobile District Attorney was able to indict Bennie Hays and his son-in-law, Frank Cox, for murder; their trial, scheduled to begin in February, will complete Beulah Mae Donald’s long and painful campaign to insure that her son’s lynching will be the last Alabama will ever see.

In the 1920′s, at the height of its popularity, the Klan had about 5 million members, more in the North than in the South; in that decade alone, Klansmen lynched as many as 900 blacks. The modern Klan has, by contrast, only about 5,000 to 7,000 members — and they are split into four groups, with no national leader. Michael Donald’s murder, the first Klan killing in Alabama in years, was more an expression of impotent rage than it was testimony to a resurgence of the white-sheeted Klan.

In the 1970′s, if the Mobile Klansmen were known for anything, it was for the business cards they printed up and handed out to the elderly ladies they helped across downtown streets. But there were still reasons they might believe they could kill a black in Mobile and go free.

Although about one-third of Mobile’s population is black, not a single one was elected to Mobile’s top governing body from 1911 to 1985. In the mid-1970′s, when a police squad was formed to prevent robberies, minority leaders charged that its real purpose was to harass blacks. In 1977, their belief gained credibility when members of this squad took an innocent black man into custody and encouraged him to confess to a burglary by putting a rope around his neck, tossing it over a tree and pulling him onto his tiptoes. The squad was disbanded, but race relations didn’t improve significantly.

As Mrs. Donald recounted her story on a sweltering summer afternoon, one grandchild rested on her couch. Another came in from the dusty yard to ask for a cold drink. ”You have water, now, you hear,” Mrs. Donald told him. ”You can’t go on drinking all my juice like you do.” She loved this boy, she explained to her visitor, but she was having trouble teaching him that the family’s resources are limited — she has not yet received any money from the Klan, and supports herself on $400 a month from Social Security and what little she makes working with retarded children. ”He complained that he’s going back to school without any new clothes,” she said. ”I told him, ‘Well, you may not get any.’ ”

Michael never looked to his mother to provide for him, Mrs. Donald said. From early childhood, ”If he came home and I was lying down, he’d know something was wrong, and he’d do little things to help — that’s the kind of boy he was.” Michael worked hard at trade school, gave his mother most of the money he made and played basketball on a community team. Smoking, she said, was his only vice. ”I told him not to smoke,” she recalled. ”He’d say, ‘I’m going to college. Can’t I have a cigarette?’ ”

Considering the kind of boy he was, Mrs. Donald knew that Michael had done nothing to provoke his murder; from the beginning, she suspected that the Klan was involved. So did Winston J. Orr, the veteran Mobile policeman who was, from 1981 to 1984, Chief of Police. But Orr was working against a number of factors that made a thorough investigation unlikely. In the early 1980′s, Mobile had one of the highest per capita murder rates in America — and no homicide squad. To make matters worse, Orr’s detectives ignored the fact that on the night of the murder, Klansmen had burned a cross on the Mobile County Courthouse lawn. Instead, they speculated that Michael Donald might have been having an affair with a white co-worker at The Mobile Press Register, where he’d had a part-time job. Or, they thought, he might have been involved in a drug deal that went sour.

Mrs. Donald was so eager to help the police that she allowed them to search Michael’s room for drugs. They tore the room apart — and found none. In June 1981, when their investigation fizzled and the three initial suspects were released, one of Beulah Mae Donald’s daughters and some friends picketed the courthouse. In August, Michael Figures, her attorney, organized a protest march. The Rev. Jesse Jackson came to Mobile to lead it. ”Don’t let them break your spirit,” he told the 8,000 marchers. But that summer, as Mrs. Donald prayed for the Lord to take her away, she had only one consolation. At least, she told herself, Michael hadn’t suffered the fate of so many murdered black men — his body hadn’t been thrown in the river.

Figures’s request arrived in Washington just as the Justice Department was thinking of closing the case. ”As an act of appeasement to me — or to convince me that a second investigation would come to the same conclusion — I was allowed to work with a second F.B.I. agent, James Bodman,” Figures recalls. ”I’ll never forget the first thing Bodman said. He asked me, ‘Why the hell do you want to reopen this can of worms?’ But then he got interested in it, and we worked on it every day. We had lunch together, we talked at night — people started calling us ‘the odd couple.’ ” In a sense, they were; both are from the deep South, but Figures is black, and Bodman is white.

After hearing a lot of lies and following many unproductive leads, Figures and Bodman uncovered one key fact: On the night of the murder, Tiger Knowles had returned to Bennie Hays’s house with blood on his shirt. With this new evidence, the Justice Department convened an investigative grand jury in Mobile. Incredibly, the Klansmen called to testify did not bring lawyers with them. In short order, one witness told the grand jury that young Henry Hays had admitted everything to him. This got back to Tiger Knowles, who began to worry that Henry Hays would confess — and, by trading testimony against Knowles for a reduced sentence, leave him bearing the greater burden of guilt.

In June of 1983, Knowles confessed to F.B.I. agent Bodman. After pleading guilty to violating Michael Donald’s civil rights, he was placed in the Federal witness protection program — a fairly standard accommodation for Klan informers — and sentenced to life in prison. In December, when Henry Hays was tried for capital murder, Knowles appeared as a prosecution witness.

Largely on the strength of his testimony, a jury of 11 whites and one black found Hays guilty and sentenced him, too, to life in prison. That didn’t seem sufficient punishment to Judge Braxton Kittrell Jr., who rejected the sentence in February 1984 and directed that Henry Hays be electrocuted. In 1986, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals set aside the death sentence. Later that year, however, the Alabama Supreme Court upheld Judge Kittrell’s decision. ”We cannot imagine,” the justices wrote, ”a case in which the death penalty is more justified.”

Henry Hays has a surprising ally in his struggle not to die in the electric chair. ”You can’t give life, so why take it?” asks Beulah Mae Donald. ”You kill an innocent person, that person stays with you day and night.”

Dees’s business career began at the University of Alabama when his mother sent him a birthday cake. That inspired Dees to send postcards to his schoolmates’ parents, asking if they’d like his ‘Bama Cake Service to deliver birthday cakes to their sons and daughters. ”We got 25 percent response,” Dees says. ”You couldn’t do that in the real world.” After graduating from the University of Alabama law school, Dees formed a direct-mail publishing company that eventually shipped 5 million cookbooks a year. He sold his company in 1970, then turned his attention to politics.

”I got interested in George McGovern strictly because of his views on Vietnam,” Dees says. He and a colleague wrote a seven-page letter for the candidate. ”Everybody laughed at it, said it was too long. McGovern said he couldn’t send it out. I said O.K., but I mailed 350,000 copies anyway. In direct mail, a good response is a 1 to 2 percent return; our letter pulled 17 percent, with an average contribution of $25.”

In the 1972 Presidential campaign, Dees’s letters garnered an unheard-of $24 million. Dees asked only for permission to use McGovern’s mailing list to approach potential contributors to his Southern Poverty Law Center. The center became active in death row cases and defended the rights of poor workers, white and black, who were felt to be victims of discrimination.

In 1979, Dees and Bill Stanton, the center’s research director, took on their first case involving the Klan. They became interested in the possibility of finishing off the Klan through civil litigation, and, to help law enforcement officials, they founded Klanwatch, an investigative unit that tracks Klan activities and publishes a newsletter. Klansmen noticed; the S.P.L.C. became the Klan’s favorite opponent.

In 1983, Klansmen torched S.P.L.C. headquarters in Montgomery; in 1984, when Denver talk-show host Alan Berg was murdered by a far-right fanatic, Dees was No. 2 on the killer’s hit list. In that same year, Louis Beam, a leader of a paramilitary Klan, challenged Dees by registered mail to a duel. ”Your mother,” he wrote, in part, ”why I can just see her now, her heart just bursting with pride as you, for the first time in your life, exhibit the qualities of a man.” Then Beam ”visited” the S.P.L.C. in an apparent effort to intimidate Dees.

From its new headquarters, dubbed the Southern Affluence Law Center because of its stylish glass-and-steel architecture, the S.P.L.C. undertook its most massive anti-Klan project in 1984 — using Mrs. Donald’s civil suit to dismantle Robert Shelton’s branch of the Klan. Shelton’s men had been involved in the beating of Freedom Riders at the Birmingham bus station in 1961, in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham in 1963 and in the shooting of Viola Liuzzo near Selma in 1965. The challenge for Dees, Stanton and S.P.L.C. investigator Joe Roy was to locate former Klansmen who would testify that they were acting under orders when they participated in those beatings and killings — and, if possible, convince Klansmen involved in more recent racial incidents to come forward.

In the 18 months it took to prepare the case, Beulah Mae Donald says, Morris Dees didn’t neglect her. ”We didn’t meet until the trial, but Morris and I would talk on the phone. He’d say, ‘You still ready to go through with this?’ And he did everything possible — he sent $35, $50 every few weeks. He helped when we needed it.”

Although Mrs. Donald hadn’t attended the 1983 trial, she decided to push herself and go to the civil trial. ”If they could stand to kill Michael,” she reasoned, ”I can stand to see their faces.” But she couldn’t look at Tiger Knowles, the first witness, as he gave the jurors an unemotional account of the events leading up to the murder. And she cried silently when Knowles stepped off the witness stand to demonstrate how he helped kill her son.

Mrs. Donald was more composed when former Klansmen testified that they had been directed by Klan leaders to harass, intimidate and kill blacks. She had no difficulty enduring defense witnesses — the six Mobile Klansmen and the lawyer for the United Klans of America cross-examined Dees’s witnesses, but called none of their own. Just four days after the trial had started, it was time for the closing arguments.

At the lunch break on that day, Tiger Knowles called Morris Dees to his cell. He wanted, he said, to speak in court. ”Whatever you do, don’t play lawyer,” Dees advised him. ”Just get up and say what you feel.”

When court resumed, the judge nodded to Knowles. ”I’ve got just a few things to say,” Knowles began, as he stood in front of the jury box. ”I know that people’s tried to discredit my testimony…I’ve lost my family. I’ve got people after me now. Everything I said is true… I was acting as a Klansman when I done this. And I hope that people learn from my mistake… I do hope you decide a judgment against me and everyone else involved.”

Then Knowles turned to Beulah Mae Donald, and, as they locked eyes for the first time, begged for her forgiveness. ”I can’t bring your son back,” he said, sobbing and shaking. ”God knows if I could trade places with him, I would. I can’t. Whatever it takes — I have nothing. But I will have to do it. And if it takes me the rest of my life to pay it, any comfort it may bring, I hope it will.”

By this time, jurors were openly weeping. The judge wiped away a tear.

”I do forgive you,” Mrs. Donald said. ”From the day I found out who you all was, I asked God to take care of y’all, and He has.”

Four hours later, the jury announced its $7 million award.

Soon, she said, the Klan building will be sold. The Klan’s money will make her too prosperous to remain in this housing project. Then she will have to leave her $94-a-month apartment, with its cinderblock walls, steep steps and sad memories. Even now, she says, her daughters are looking for a new apartment, convenient to her church and most of her 32 grandchildren.

In her new home, her family hopes, she’ll find some peace. Mrs. Donald, now 68, doesn’t have much expectation of that. ”When the trial was over, the jurors came down and told me, as people do, that they felt for me,” she says. ”But the verdict didn’t make me feel better. What happened to Michael — I live it day and night. I was just surprised that a white jury could do this.”

For all her sorrow, Beulah Mae Donald emphasizes that she won’t succumb to bitterness. ”What is a dream to me is that money comes out of this,” she says, contemplating the irony of human loss and monetary gain. ”I don’t need it. I live day to day, like always. But there’s some sad people in the world who don’t have food to eat or a decent place to stay. I’ve been there. I know what it means to have nothing. If the Klan don’t give me a penny, that’s O.K. But if they do, I’m going to help a lot of people who don’t have none.”

The Aftermath

Morris Dees, co-founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center, is now its chief trial counsel.

Henry Hayes, age 42, was executed in Alabama’s electric chair on June 6, 1997. He was the first white person executed for the murder of an African American in Alabama since 1913.

Tiger Knowles was sentenced to 10 years to life imprisonment for his part in the killing.

Frank Cox, 28, was sentenced to life in prison.

Bennie Hays had a heart attack and collapsed in the courtroom during his first trial, causing a mistrial. He died before he could be retried.

Robert Shelton died of a heart attack in 2003. He was 73.

James F. Bodman died in 1991.

Thomas Figures is a lawyer in Mobile.

In 2006, Mobile named a street after Michael Donald. Sam Jones, Mobile’s first black mayor, presided over the dedication ceremony.

Jesse Kornbluth is the co-founded Bookreporter.com. From 1997 to 2002, he was Editorial Director of America Online. In 2004, I launched HeadButler.com.

This piece was reprinted by EmpathyEducates with permission or license. We thank the Author, Jesse Kornbluth for his kindness, research, heartfelt accounts of history, caring and for sharing. We are honored.