Project Description

Unemployment from a Child’s Perspective

INTRODUCTION

When a parent loses a job, the entire family is affected, including the children. Money is suddenly tighter, and what was affordable last month, no longer is. Even children who are too young to be aware of financial adjustments may pick up on a change in the family atmosphere. Adults may be arguing more frequently, and parents may speak more sharply to their children. While children may benefit from their parents spending more time at home, the downsides of parental unemployment—the loss in family income and increase in parental stress—tend to overshadow such potential benefits, leaving children worse off when one of their parents loses a job.

Millions of American lost their jobs during the Great Recession, and millions were still unemployed in 2012. As a result, millions of children have experienced parental unemployment recently; 6.2 million children still lived in families with unemployed parents in an average month of 2012. The number rises higher—to 12.1 million, or one in six children—under broader measures of parental under- or unemployment. Because children are often overlooked in official unemployment statistics, this brief examines unemployment from a child’s perspective. It addresses the following questions:

- How many children are affected by parental unemployment?

- How does parental job loss affect children?

- Who are the children of the unemployed?

- Where do the children of the unemployed live?

- To what extent are families with children covered by unemployment insurance?

The brief concludes with a review of policies affecting the safety net for children of the unemployed. It is part of a series of issue briefs examining the impact of the recession on children. 1

HOW MANY CHILDREN ARE AFFECTED BY PARENTAL UNEMPLOYMENT?

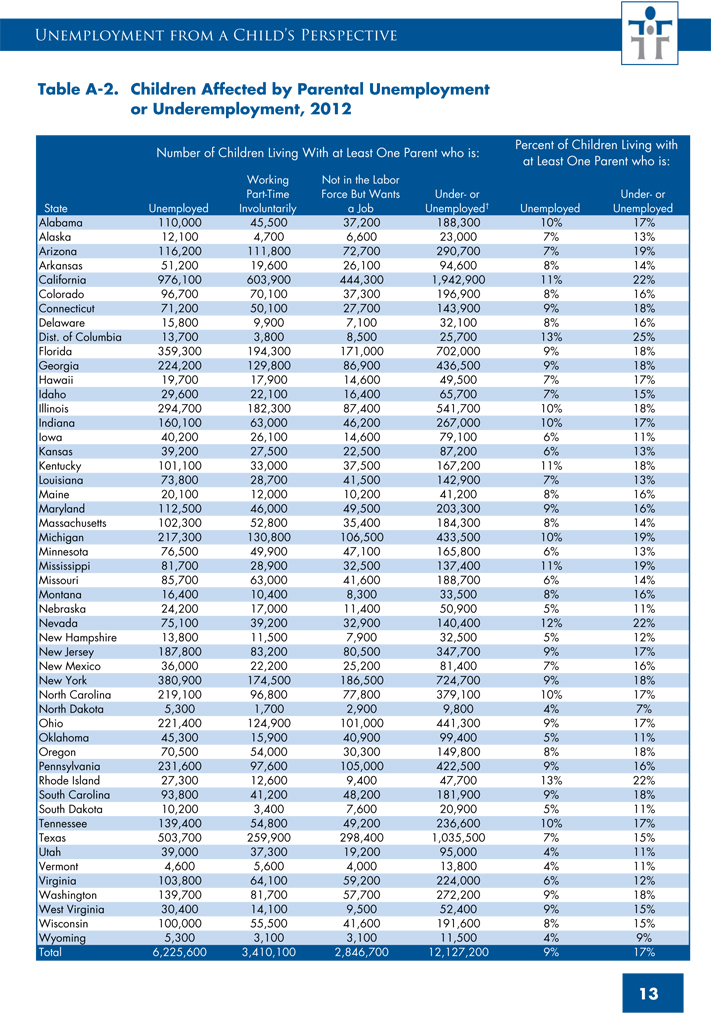

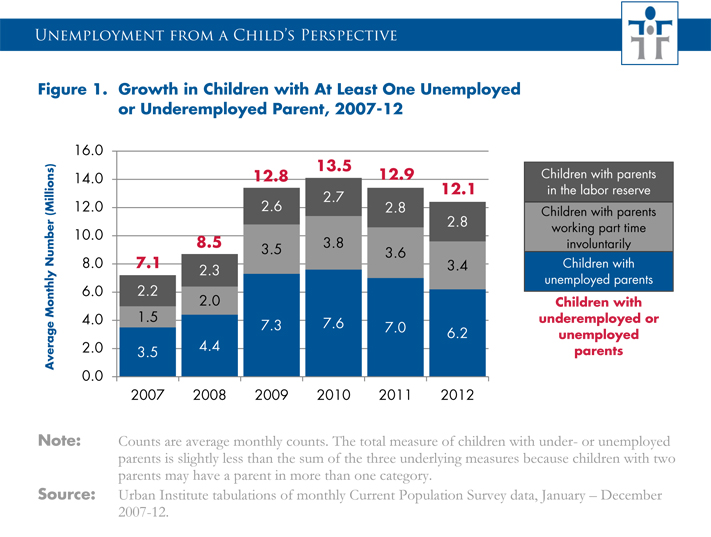

More than one in six children, or 12.1 million, were affected by parental unemployment and underemployment in 2012, under a broad measure that counts not only children with at least one unemployed parent (6.2 million children) but also children living with at least one parent who had to settle for part-time work because of slack business conditions or difficulty finding full-time work (3.4 million) and children living with at least one parent who wants a job but is not actively seeking work and is classified by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as being in the labor reserve (2.8 million).2

As shown in figure 1, each of these measures of unemployment grew substantially between 2007 and 2010, with only modest improvement since the peak of the recession. For example, the average monthly number of children with at least one unemployed parent more than doubled between 2007 and 2010 (from 3.5 to 7.6 million); while it has declined since then, it is still much higher than before the recession (6.2 versus 3.5 million). The recession also has led to a substantial increase in parents who are working part time, involuntarily, for economic reasons. Compared to before the recession, more than twice as many children in 2012 are living with parents who would prefer to clock a full 40-hour workweek but have seen their hours cut or can’t find full-time jobs and must work part time instead (3.4 vs. 1.5 million). The recession has had less of an impact on the number of children with parents who want a job but are no longer actively seeking work, although this group of parents has continued to grow (from 2.2 million in 2007 to 2.7 million in 2010 and 2.8 million in 2012).

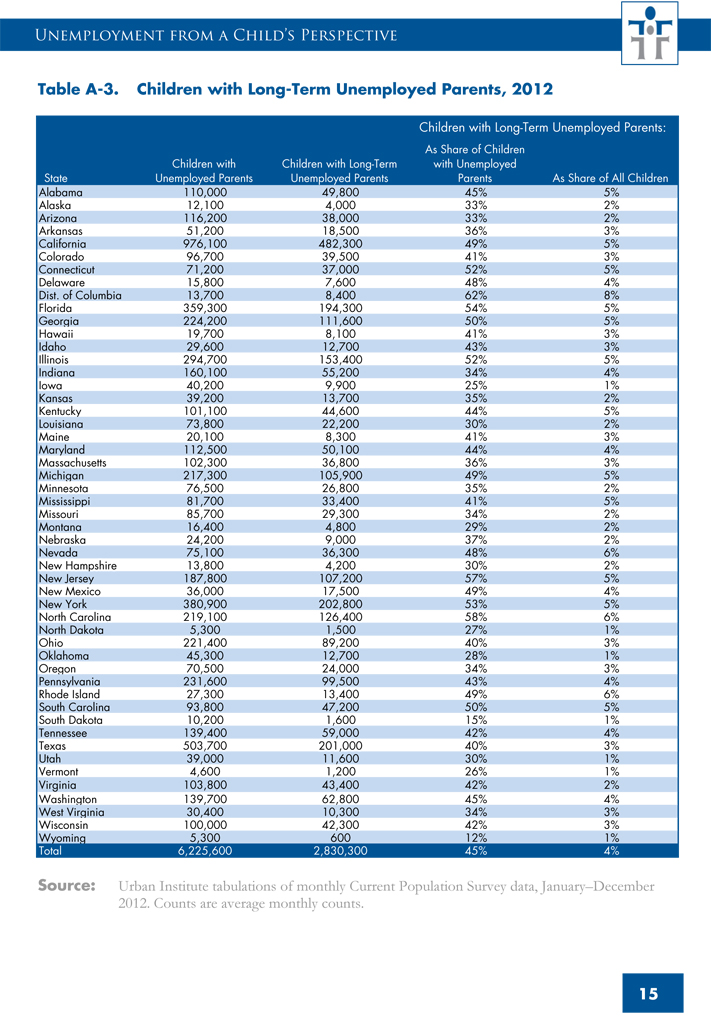

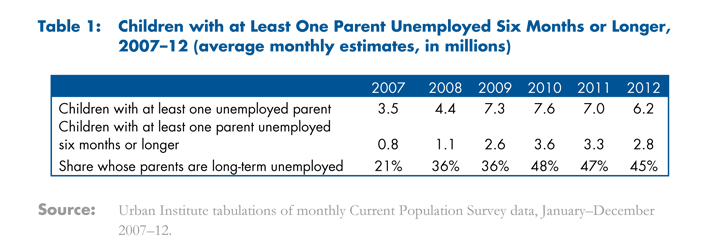

Of particular concern has been the dramatic growth in unemployment spells that last six months or longer. As shown in table 1, the number of children living with a parent who has been looking for work for six months or longer has more than tripled, from 0.8 million in 2007 to 2.8 million in 2012. This represents almost half (45 percent) of all children living with unemployed parents. Families with such long periods of unemployment have much higher risks of poverty and financial hardship than families where the unemployed parent finds another job more quickly.

While most of this brief focuses on children living with unemployed parents, youth unemployment has also risen sharply during the recession. The number of unemployed youth age 16 to 24 rose from 2.6 million in July 2007 to 4.4 million in July 2009 and 2010, before dropping slightly to 4.0 million in July 2012. This past July, the unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds was 17.1 percent, below the 19.1 percent rate of July 2010 but still far above the 10.8 percent rate back in 2007.

HOW DOES PARENTAL JOB LOSS AFFECT CHILDREN?

One of the first impacts of parental job loss is that families have fewer financial resources available to meet their regular monthly expenses and support their children’s development. Reductions in family income are more likely to threaten children’s development if the family’s income falls below the poverty level, as may occur if income was low before the job loss, the unemployed parent is the sole breadwinner, or the spell of unemployment lasts for many months.

In their analysis of family income and poverty after unemployment, Zedlewski and Nichols (2012) report that poverty nearly triples among parents who remain out of work for six months or longer, even after counting the value of benefits from safety net programs. Specifically, the poverty rate for long-term unemployed parents, who represented 45 percent of the authors’ sample, rose from 12 percent before the job loss to 35 percent during their period of unemployment.3 Children in poverty may lack the resources that support healthy development if the family has trouble providing nutritious meals, safe child care settings, access to learning materials, and other resources that promote healthy development or if the family moves into crowded housing or neighborhoods with more crime and air and noise pollution.4 As a result, living in poverty can have detrimental effects on children’s long-term well-being, particularly if children live in poverty while young or for prolonged periods.5

Job loss also can have a negative impact on family dynamics. A body of research dating back to the Great Depression finds evidence of increased parental irritability and depression and higher levels of family conflict after parental job loss, with spillovers into less supportive and more punitive parenting behaviors. Developmental psychologists emphasize the links between economic stress and parents’ mental health, and further links to parents’ responses to their children and children’s well-being.6 Finally, in addition to lower financial resources and changes in family processes, parental job loss may lead to changes in adolescents’ attitudes toward work, as they see their parents’ lack of success in the labor market.

One of the earliest signs that children are not doing well is their school performance. Several studies have documented lower math scores, poorer school attendance, and a higher risk of grade repetition or even suspension or expulsion among children whose parents have lost their jobs.7 For example, Stevens and Schaller (2011) find that parental job loss increases the chances a child will be held back in school by nearly 1 percentage point a year, or 15 percent.

Not all families are affected equally. Some studies find differences between paternal and maternal job loss, with larger negative effects on both family conflict and child outcomes when the father rather than the mother loses the job.8 Other studies find larger effects among families with less income, suggesting that poverty and economic hardship after job loss may explain some of the negative effects. 9

The adverse effects of parental job loss can persist into a child’s adult life. For example, Coelli (2010) reports that low-income youth whose parents lose their jobs have lower rates of college attendance. Moreover, Oreopoulos, Page, and Stevens (2008) find that boys whose fathers lost their jobs when plants closed in the early 1980s had annual earnings about 9 percent lower than similar children whose fathers did not experience such job losses.10 Such long-term effects may result from a combination of reduced family income at critical times (such as when the youth is making plans for postsecondary education), the detrimental effects of family conflict and harsh discipline behaviors, and changes in the child’s aspirations for success in the labor market.

WHO ARE THE CHILDREN OF THE UNEMPLOYED?

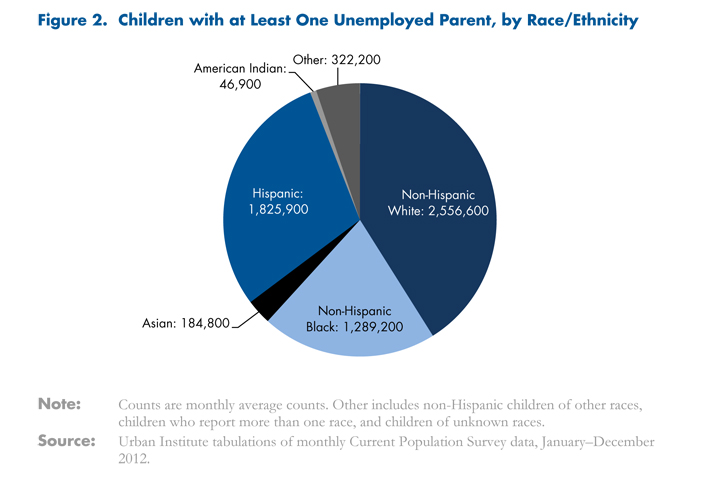

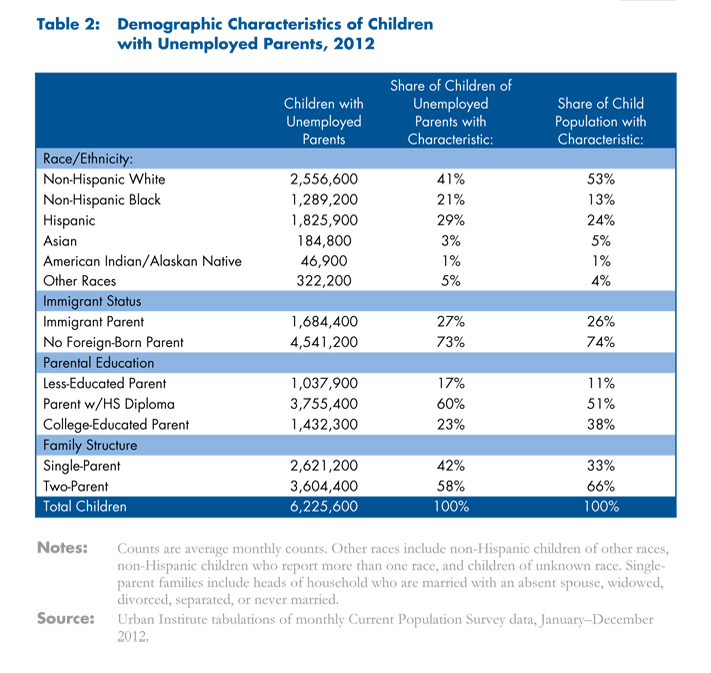

Children affected by parental unemployment come from diverse family backgrounds. Of the 6.2 million children living with unemployed parents in an average month of 2012, 2.6 million are non-Hispanic white, 1.3 million are non-Hispanic black, 1.8 million are Hispanic, 185,000 are Asian, 47,000 are American Indians and Alaskan natives, and 322,000 are children of other races, including children of more than one race (figure 2). About a quarter of children of the unemployed are children of immigrants, similar to the percentage of children of immigrants among the general population (see table 2). Slightly less than one-fifth are children whose parents lack high school diplomas, three-fifths are children of high school graduates, and nearly one- quarter are children of college-educated parents. Finally, two-fifths are children in single-parent families, and three-fifths are children in two-parent families.11

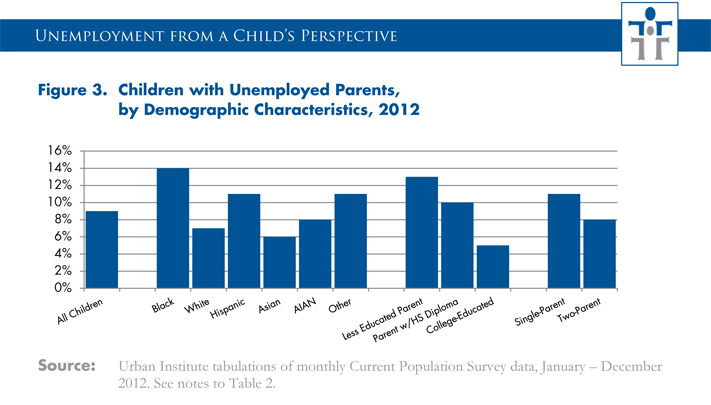

While children of the unemployed include children of varied family backgrounds, some demographic groups are more heavily represented than others. Black children are twice as likely to live with unemployed parents as white children (14 percent versus 7 percent), as shown in figure 3. Children of college-educated parents are less likely to be affected by unemployment than other children (5 percent for college-educated parents versus 10 percent for high school graduates and 13 percent for parents without high school diplomas). And, children in single-parent families are more likely to live with an unemployed parent than children in two-parent families (11 percent compared with 8 percent).

In their research on unemployed parents, Zedlewski and Nichols (2012) find similar patterns by demographic characteristics. However, their research shows interesting patterns regarding length of unemployment spells. While parents without high school education and Hispanic parents experience unemployment more often than parents in other education and racial/ethnic groups, they tend to be out of work for shorter periods than other unemployed parents.12

WHERE DO CHILDREN OF THE UNEMPLOYED LIVE?

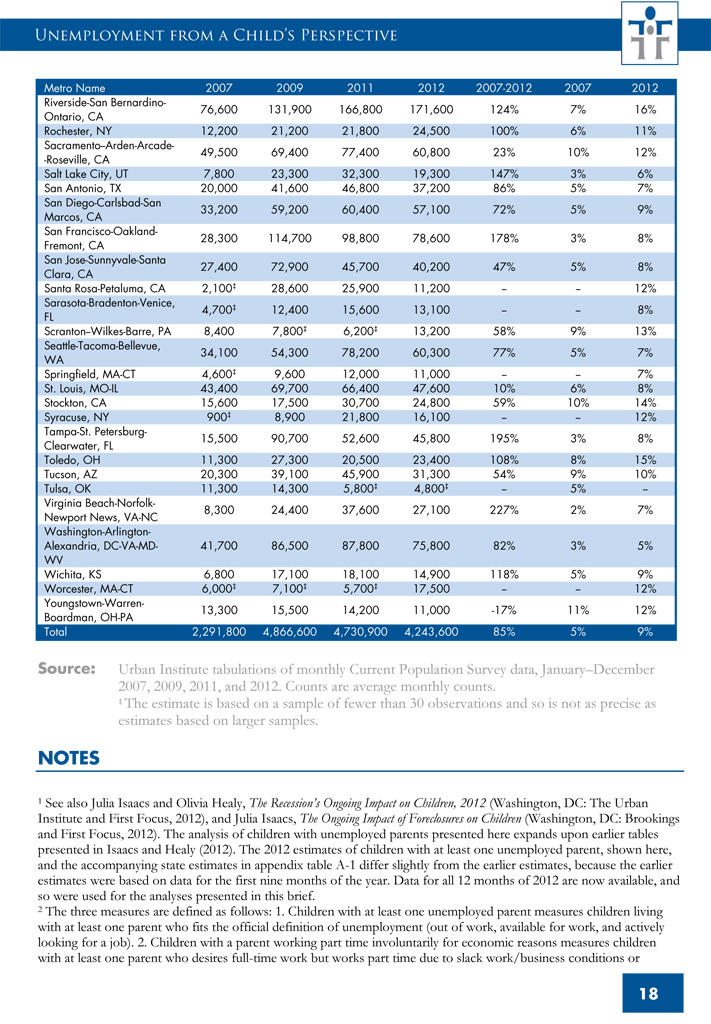

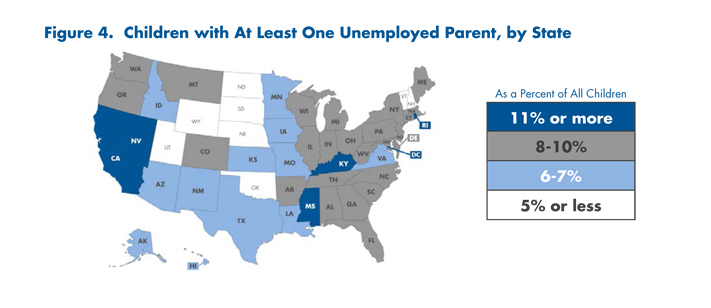

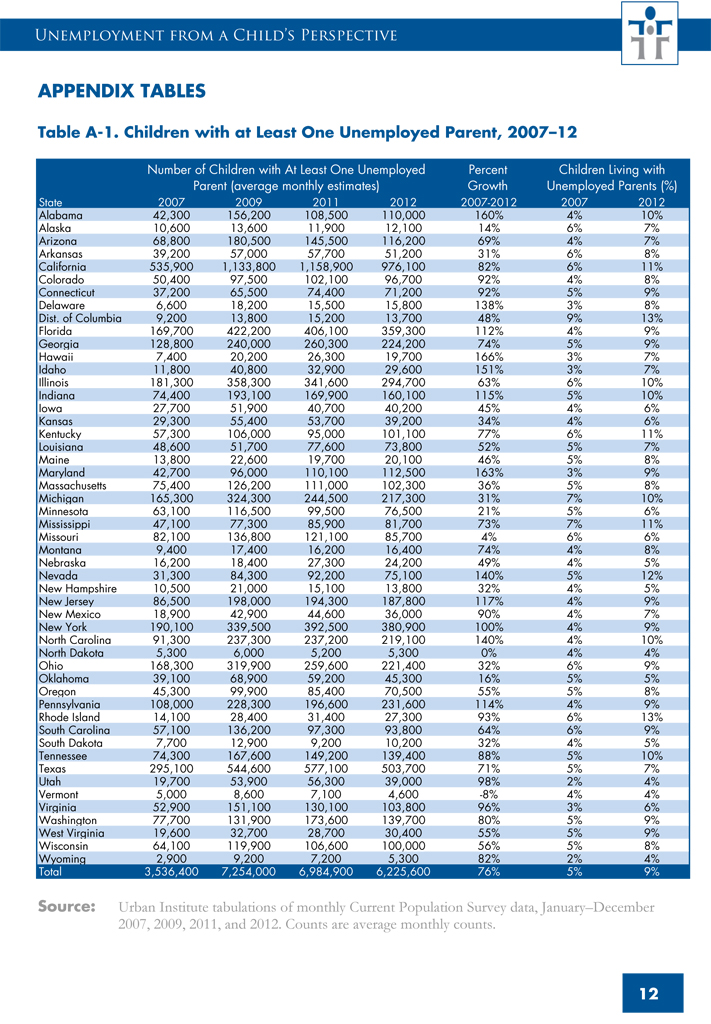

Children with unemployed parents live throughout the country. According to the most recent data, nearly 1 million (976,000) of them live in California, reflecting both the size of the state’s population and the severity of its economic problems. More than one in ten children in California (11 percent) live with at least one unemployed parent. Nationwide, an average of 9 percent of children live with at least one unemployed parent, with the percentage ranging from under 4 percent in North Dakota and Vermont to 13 percent in the District of Columbia and Rhode Island, as shown in figure 4, below, and appendix table A-1.13

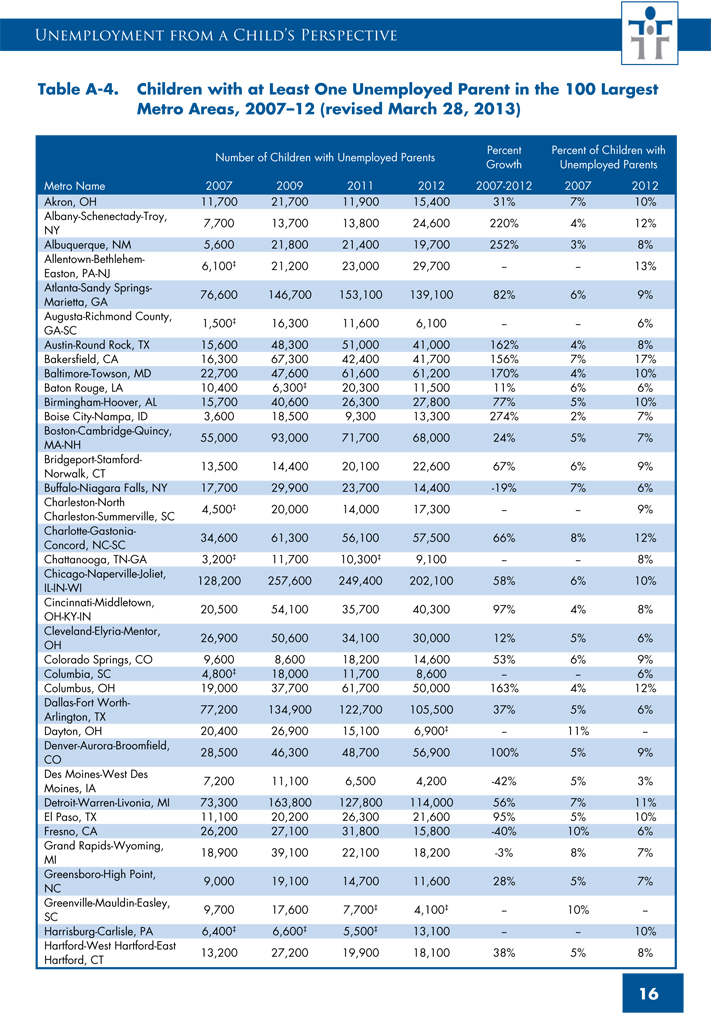

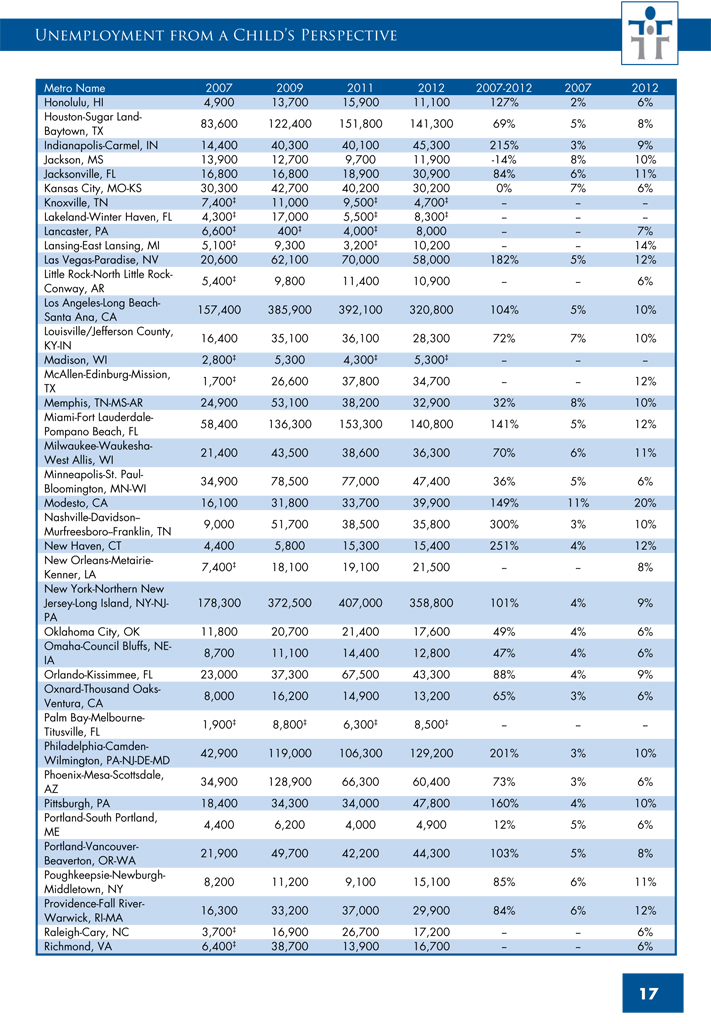

While the depth of the problem varies across states, all states saw a sharp rise between 2007 and 2009 in the number of children living with at least one unemployed parent. In most states, the numbers have remained persistently high since then. The 2012 data show more children living with unemployed parents today than before the recession started in all but two states. (The two exceptions are North Dakota and Vermont, already flagged above as having very low shares of their child population in families with unemployed parents.) In fact, 12 states have more than twice as many children with unemployed parents than they did five years ago: Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Maryland, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania (these states have 2007–12 growth rates of 100 percent or more, as shown in appendix table A-1).

Further measures of unemployment by state and in large metropolitan areas are provided in the appendix tables. For example, the number of children affected by parental unemployment or underemployment in California rises to more than 1.9 million, or 22 percent of the state’s child population, when considering children with at least one unemployed parent along with children whose parents are working part-time involuntarily or have dropped out of the labor force but say they want to work (see appendix table A-2). Children living with parents out of work for more than six months are a particularly large share (50 percent or more) of children of the unemployed in Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina and South Carolina (see appendix table A-3).

Statistics by large metropolitan area indicate that one-fifth (20 percent) of the children in the Modesto, California, metropolitan area are living with at least one unemployed parent, with unusually high percentages also found in Bakersfield, California (17 percent), Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, California (16 percent), and Toledo, Ohio (15 percent) (see appendix table A-4).

TO WHAT EXTENT ARE FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN COVERED BY UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE?

Unemployment benefits can cushion the adverse effects of unemployment—and help stabilize the economy during economic downturns—by providing families with cash benefits to offset some of their lost wages. Exact rules and benefit formulas for regular benefits under the joint federal-state program vary by state, but most states replace up to half of a person’s average weekly wages, up to state-established maximums.14

When regular benefits are exhausted (after 26 weeks in most states), unemployed workers can apply for extended benefits, under either the regular Extended Benefits program or the Emergency Unemployment Compensation Program, which was enacted in 2008 and recently extended through January 1, 2014, to provide additional assistance during the current economic downturn.

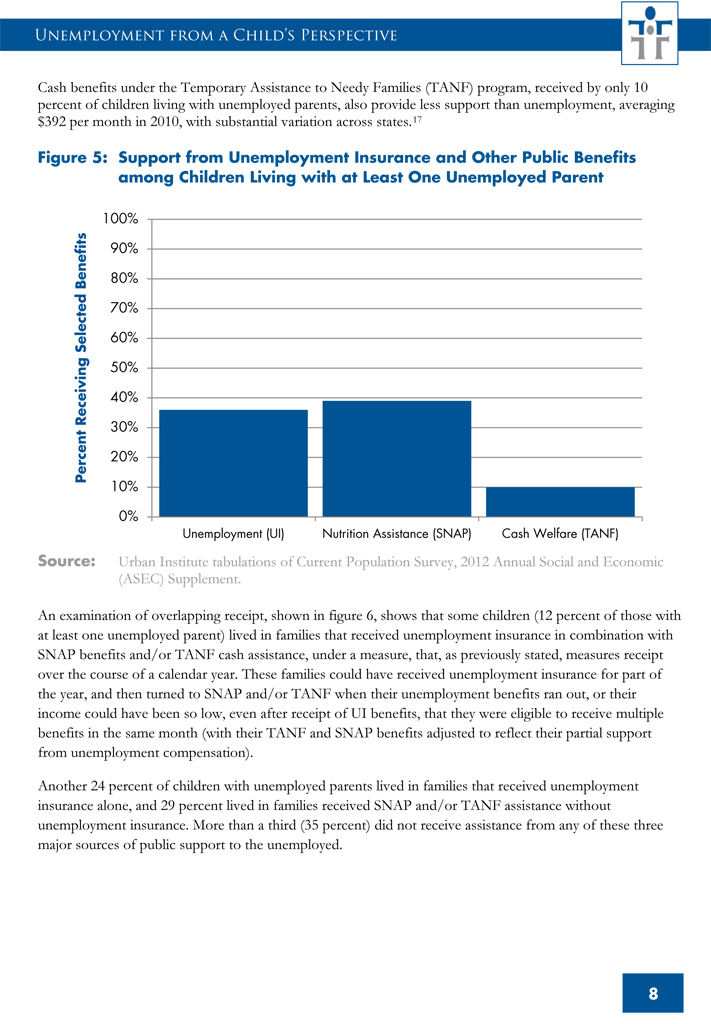

Receipt of unemployment benefits is limited, however, to individuals who apply for benefits and who meet both financial and nonfinancial qualifying rules in their state. As shown in figure 5 below, only 36 percent of children whose parents were unemployed at some point in 2011 lived in families that received unemployment insurance (UI) benefits during that calendar year.15

In fact, children living with at least one unemployed parent were more likely to receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits (39 percent) than they were to receive unemployment benefits. Yet SNAP benefits (formerly known as food stamps) do not provide families anywhere near the level of support as unemployment benefits, and SNAP can only be used on food items; in July 2012, SNAP monthly benefits averaged about $278 per household, less than the average weekly benefit of $299 for unemployment benefits (the monthly equivalent of $1,286).16

Cash benefits under the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) program, received by only 10 percent of children living with unemployed parents, also provide less support than unemployment, averaging $392 per month in 2010, with substantial variation across states.17

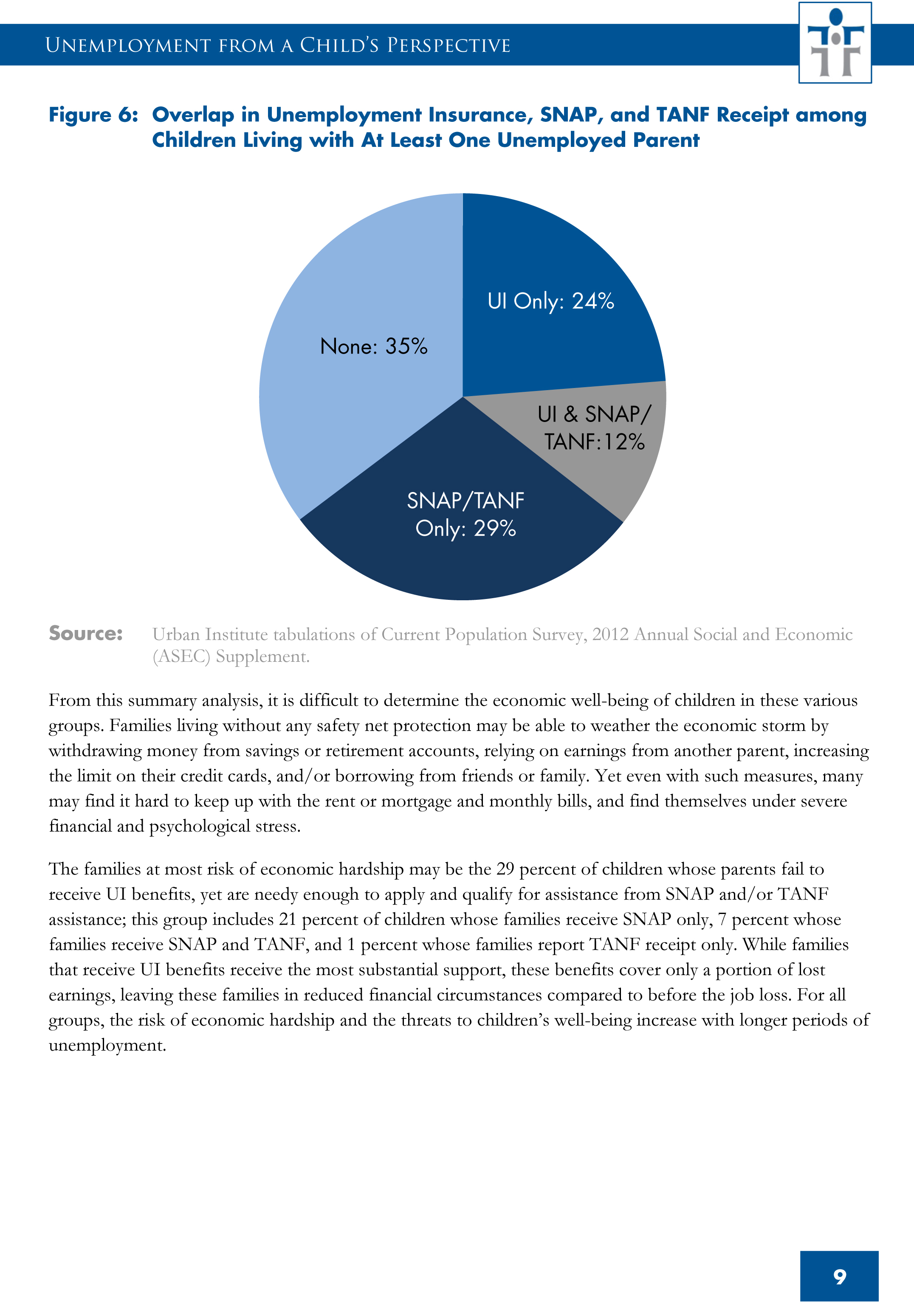

An examination of overlapping receipt, shown in figure 6, shows that some children (12 percent of those with at least one unemployed parent) lived in families that received unemployment insurance in combination with SNAP benefits and/or TANF cash assistance, under a measure, that, as previously stated, measures receipt over the course of a calendar year. These families could have received unemployment insurance for part of the year, and then turned to SNAP and/or TANF when their unemployment benefits ran out, or their income could have been so low, even after receipt of UI benefits, that they were eligible to receive multiple benefits in the same month (with their TANF and SNAP benefits adjusted to reflect their partial support from unemployment compensation).

Another 24 percent of children with unemployed parents lived in families that received unemployment insurance alone, and 29 percent lived in families received SNAP and/or TANF assistance without unemployment insurance. More than a third (35 percent) did not receive assistance from any of these three major sources of public support to the unemployed.

From this summary analysis, it is difficult to determine the economic well-being of children in these various groups. Families living without any safety net protection may be able to weather the economic storm by withdrawing money from savings or retirement accounts, relying on earnings from another parent, increasing the limit on their credit cards, and/or borrowing from friends or family. Yet even with such measures, many may find it hard to keep up with the rent or mortgage and monthly bills, and find themselves under severe financial and psychological stress.

The families at most risk of economic hardship may be the 29 percent of children whose parents fail to receive UI benefits, yet are needy enough to apply and qualify for assistance from SNAP and/or TANF assistance; this group includes 21 percent of children whose families receive SNAP only, 7 percent whose families receive SNAP and TANF, and 1 percent whose families report TANF receipt only. While families that receive UI benefits receive the most substantial support, these benefits cover only a portion of lost earnings, leaving these families in reduced financial circumstances compared to before the job loss. For all groups, the risk of economic hardship and the threats to children’s well-being increase with longer periods of unemployment.

STATUS OF THE SAFETY NET FOR CHILDREN WITH UNEMPLOYED PARENTS

Only 36 percent of children with unemployed parents live in families receiving unemployment insurance, 29 percent live in families who turn to SNAP and/or TANF for assistance in place of unemployment insurance and 35 percent live in families who rely on private sources of support. With so many families with unemployed workers falling through the gaps in the social safety net, it is important to review options for strengthening the social safety net for children with unemployed parents.

Prompted by federal incentives provided under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a majority of states (39 states) recently adopted reforms to modernize their state unemployment insurance programs and expand access to groups with lower coverage rates, including low-wage workers, working mothers, part-time workers, and the long-term unemployed.18 However, even with these reforms, most of which were adopted in 2009 or 2010, coverage rates remained low in 2011, as shown in figure 5.

Coverage rates could increase if more states adopted some of the modernization reforms that were encouraged under ARRA.19 Nevertheless, additional reforms may be necessary to reach disadvantaged workers and others who are not adequately covered by the current system. In the modern age, low-wage workers are more likely to work in the service sector than in factories, and job loss is less often driven by plant closings and formal lay-offs and is more often a result of workers leaving service sector jobs after struggling to combine intermittent and erratic hours with family responsibilities. Denial of unemployment benefits after such “voluntary” quits contributes to the low rates of coverage in the United States, according to research by H. Luke Shaefer (2010). He notes that one way to expand access—yet guard against enticing workers to casually quit their jobs—would be to ban benefits for a certain period (perhaps 4 to 12 weeks) after voluntary quits, rather than throughout the total spell of unemployment.20 His research also highlights the fact that many disadvantaged workers who appear eligible for unemployment do not apply for benefits, suggesting a role for public outreach or improvements to the application process. 21

While further reform of the UI system would help children of the unemployed, it may be hard to persuade state legislatures to expand access to benefits, given the strain on state unemployment trust funds during this recession. In fact, over the past three years, eight states have cut the number of weeks of regular benefit receipt, from the traditional standard of 26 weeks to durations that range from 25 weeks in Arkansas and Illinois to 20 weeks in Michigan, Missouri, and South Carolina, and varying durations depending on state unemployment rates, but possibly dipping as low as 14 weeks in Georgia and 12 weeks in Florida and North Carolina.22 Unemployed workers in these states also receive fewer weeks of extended federal benefits as a result of the reduction in state benefits; unemployed workers in North Carolina are scheduled to lose all weeks of federal benefits as of July 1, 2013, because of the radical cuts in that state program.23 The policy battle in some states, therefore, is more focused on proposals to cut back on current benefits, rather than considering ways to modernize the program to extend access to underserved populations.

At the federal level, much of the policy debate around unemployment insurance has focused on federally funded benefits to the long-term unemployed. As in past recessions, Congress has enacted a temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC) program to provide additional benefits to those who exhaust regular benefits. Although some lawmakers would like to see the program expire, and it nearly did on December 31, 2012, the number of long-term unemployed individuals is still very high, and the program was extended through the end of the end of 2013, as part of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, also known as the fiscal cliff package. However, unemployment checks to the long-term unemployed may cut by approximately 10 percent as early as April 2013 in many states, unless Congress acts to modify the sequestration provisions of the Budget Control Act of 2011.24

In addition to unemployment insurance, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program plays a major role in supporting children of the unemployed. With the rise in need during the recession, SNAP has grown; as of spring 2012 it had nearly 21.6 million children on its rolls, or more than one in four American children. 25

With the increase in recipients, some members of Congress have proposed cutting back on program spending, despite the fact that most program growth has occurred in response to the economic downturn. Both the Senate-passed and House-reported farm bills would have cut SNAP program spending, with the proposed cuts totaling $4.5 billion and $16.5 billion, respectively, over 10 years.26 Neither bill was enacted, however, and SNAP was extended through September 2013, without benefit cuts, as part of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. As Congress considers longer-term reauthorization of SNAP as part of it deliberations on the Farm Bill, the question of whether to cut back on SNAP benefits may again arise. Such cuts would further weaken the ability of the social safety net to cushion children from negative effects of parental job loss.

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program is another important component of the safety net for children with unemployed parents, although it assists many fewer children than the unemployment insurance system or the SNAP program. With its block-grant structure, the TANF program no longer plays much of a counter-cyclical role in times of economic downturn; TANF caseloads rose only modestly during this recession, in contrast to increased welfare caseloads in earlier times.27 The TANF program’s ability to help children with unemployed parents could be strengthened by modifying the program; one recent recommendation for TANF reauthorization suggests building on the experience of the TANF Emergency Fund and adding a permanent contingency fund to provide additional assistance in times of high unemployment rates.28

Finally, while this section has emphasized safety net support for children of the unemployed, what would be most helpful for many children would be policies to help their parents get new jobs. A stronger economic recovery would help many parents, but some long-term unemployed parents may need additional skills training or transitional employment to aid them in getting back to work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author appreciates the excellent research assistance of Olivia Healy and insightful comments of Megan Curran and H. Elizabeth Peters.

CORRECTION

The original version of this report released on March 25, 2013, included an error in Table A-4. This version, released March 29, 2013, corrects that error.

Page 14 intentionally blank