Project Description

Retention or Transfer? What does it mean for education systems?

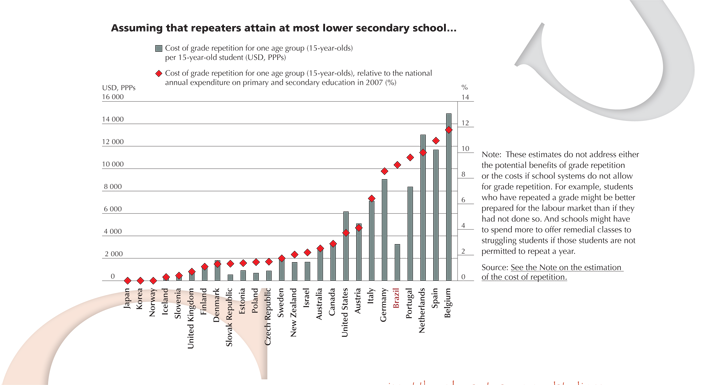

- High rates of grade repetition can be costly for countries.

- In countries where more students repeat grades, overall performance tends to be lower and social background has a stronger impact on learning outcomes than in countries where fewer students repeat grades. The same outcomes are found in countries where it is more common to transfer weak or disruptive students out of a school.

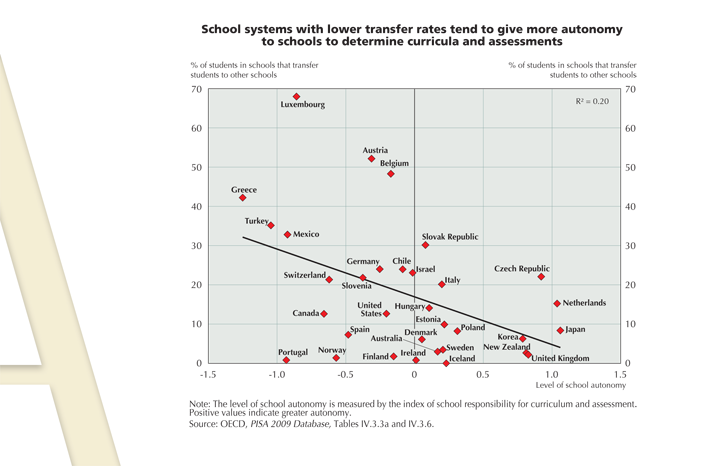

- Countries with fewer options to transfer students use other means to work with struggling students, such as giving more autonomy to schools to design curricula and assessments.

School systems handle the challenges of diverse student populations in different ways. Some countries have non-selective and comprehensive school systems that seek to provide all students with similar opportunities, leaving it to individual schools and teachers to meet the particular needs of every student. Other countries group students, whether in different schools or in different classes within schools, with the aim of serving students according to their particular academic potential, interests and/or behaviour. Having underperforming students repeat grades or transferring struggling or disruptive students to other schools are two common policies used to group students for this reason.

Grade repetition is used extensively in some countries…

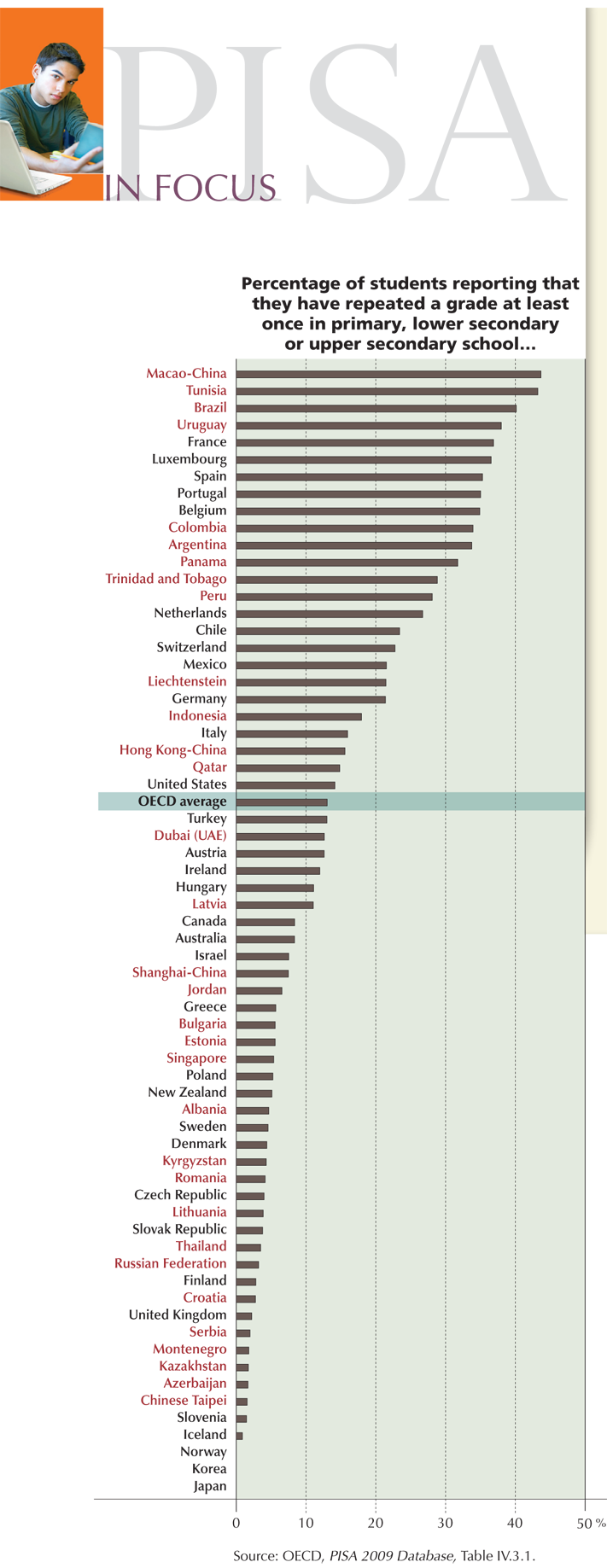

According to PISA 2009, an average of 13% of 15-year- old students across OECD countries reported that they had repeated a grade at least once: 7% of students had repeated a grade in primary school, 6% had repeated a grade in lower secondary school, and 2% had repeated a grade in upper secondary school. Over 97% of students in Finland, Iceland, Slovenia, the United Kingdom, the partner countries Azerbaijan, Croatia, Kazakhstan, Montenegro, Serbia, and the partner economy Chinese Taipei reported they had never repeated a grade; and grade repetition is non-existent in Japan, Korea and Norway. In contrast, over 25% of students in Belgium, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, the partner countries Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Panama, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Uruguay, and the partner economy Macao-China reported that they had repeated a grade.

But having students repeat grades implies some costs, including the expense of providing an additional year of education for a student, and the cost to society in delaying that student’s entry into the labor market by at least one year. Among the countries that practice grade Repetition, and that have relevant data available, in Iceland and Slovenia, the cost of using grade repetition for one age group can be as low as 0.5% or less of the annual national expenditure on primary- and secondary-school education. When that cost is converted to the cost per 15-year-old student, it is as low as USD 500 or less. In Belgium, the Netherlands and Spain, the cost is equivalent to 10% or more of the annual national expenditure on primary- and secondary-school education, and the cost per student can be as high as USD 11 000 or more. These estimates are based on the assumption that students who repeat grades attain, at most, lower secondary education. If they were to attain higher levels of education, the costs would be even greater.

When countries have to bear such high costs for grade repetition, do they at least benefit in overall performance and equity? PISA2009 shows that countries with high rates of grade repetition are also those that show poorer student performance. Some 15% of the variation in performance among OECD countries can be explained by differences in the rates of grade repetition, and students’ socio-economic background is more strongly associated with performance in these countries, regardless of the country’s wealth.

Moving students to different schools…

Transferring students to another school because of low academic achievement, behavioural problems or special learning needs is another way that education systems group students. On average across OECD countries, 18% of students attend a school in which school principals reported that the school would “very likely” transfer students for these reasons.

In Australia, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, new Zealand, Norway, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the partner countries Liechtenstein and Singapore, fewer than 3% of students attend schools whose school principals reported that the school would “very likely” transfer students for these reasons; while in Austria, Belgium, Greece, Luxembourg, the partner countries Colombia, Indonesia, Jordan, Qatar, Romania, and the partner economy Macao-China, over 40% of students attend such schools.

PISA 2009 reveals that countries in which more schools transfer students for the abovementioned reasons show poorer overall performance. In fact, over one-third of the variation in student performance across countries can be explained by the rate at which schools transfer students, regardless of the wealth of the country.

School systems that transfer students more frequently also tend to show a stronger relationship between students’ socio-economic background and performance, and a wider gap in performance between schools, even after accounting for countries’ national income. This suggests that transferring students tends to be associated with socio-economic segregation in school systems, where students from advantaged backgrounds end up in better-performing schools while students from disadvantaged backgrounds end up in poorer-performing schools. However, this does not necessarily mean that if countries abolish their transfer policies, their performance will automatically improve; PISA doesn’t measure cause and effect.

… is not the only way to accommodate diverse student populations.

Schools that don’t have the option to transfer students address the wide diversity of students’ abilities, potentials and interests in other ways. For example, school principals in countries with low rates of student transfers often report that their schools have more responsibility for establishing student-assessment policies, deciding which courses are offered, determining course content and choosing textbooks – all of which are other means of accommodating heterogeneous student populations. Across OECD countries, 20% of the variation in the rate of student transfers is related to the extent to which individual schools are responsible for their own curriculum and assessment policies.

These results suggest that, in general, school systems that seek to cater to different students’ needs by having struggling students repeat grades or by transferring them to other schools do not succeed in producing superior overall results and, in some cases, reinforce socio-economic inequities. Teachers in these systems may have fewer incentives to work with struggling students if they know there is an option of transferring those students to other schools. These school systems need to consider how to create appropriate incentives to ensure that some students are not “discarded” by the system.

Bottom line: Some policies that are used to group students according r academic potential, interests or behaviour, such as having students t grades or transferring students to other schools, can be costly for school systems and are generally not associated with better student performance or more equitable learning opportunities.

For more information

Contact Miyako ikeda (Miyako.Ikeda@oecd.org)

See PISA 2009 Results: What Makes a School Successful? Resources, Policies and Practices (Volume IV), and Note On The Estimation Of The Cost Of Repetition